Features

Training

Trainer’s Corner: February 2013

For almost two decades, the tragic story of four volunteer firefighters has haunted me. This column is in memory of René Desharnais, Martin Desrochers, Raynald Dion and Raymond Michaud.

February 1, 2013

By Ed Brouwer

For almost two decades, the tragic story of four volunteer firefighters has haunted me. This column is in memory of René Desharnais, Martin Desrochers, Raynald Dion and Raymond Michaud. I hope to raise awareness of the hazards present when a liquid petroleum (LP) gas tank is involved in or exposed to fire.

At 9:02 a.m. on June 27, 1993, the Warwick Volunteer Fire Department in Quebec responded to a report of a barn fire. When firefighters arrived at about 9:12 a.m., they found a large cattle barn ablaze. During size-up, a 4,000-litre propane tank was found close to the involved barn. The relief vents were operating on the tank, shooting flames more than five metres into the air.

Firefighters began to apply water to the exposed LP tank in an effort to cool it. Suddenly, the tank split into two large pieces. The blast sent one of the pieces into an open field, while the other piece travelled more than 45 metres (148 feet), striking a fire engine, and continuing for another 230 metres (755 feet), at which point it hit a vehicle parked on the road, trapping an occupant.

Three firefighters were killed when the piece of the tank struck the engine – they were donning protective equipment and preparing hose lines. The fourth firefighter was killed when he was thrown 45 metres as the piece slammed into the engine.

The blast also injured three firefighters and four civilians, including the occupant of the vehicle on the road.

Since 1993, at least two similar incidents involving LP gas tanks in a farm setting have resulted in the deaths of four more firefighters. The first incident occurred in Burnside, Ill., and resulted in two fatalities on Oct. 2, 1997. Then on April 9, 1998, two volunteer firefighters died in Albert City, Iowa, and six responders were injured when a burning LP gas tank exploded in a boiling liquid expanded vapour explosion, or BLEVE.

In each case, the tanks’ relief valves were operating when firefighters arrived, but they couldn’t stop flames from impinging on the tanks and weakening the tank shells. In each case, tanks ruptured in BLEVEs that sent pieces of metal flying at high velocities in random directions, killing those in their path.

A case study of the explosion in Warwick, Que., which can be found online at ncsp.tamu.edu/reports/IPR/warwick.htm, explains, “A BLEVE occurs when the temperature of the liquid and vapour within a confined tank or vessel is raised, often by an external fire, to such a point that the increasing internal pressure of the liquefied gas inside can no longer be contained and the vessel explodes. This rupture of the confining vessel releases the pressurized liquid and allows it to vaporize almost instantaneously. If the liquefied gas is flammable, such as propane, the large vapour cloud produced is almost always ignited. Ignition usually occurs either from the original external fire that caused the BLEVE or from some electrical or friction source created by the blast or shrapnel effect of the container rupture.’’

The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board investigated the April 9, 1998 incident at the Herrig Turkey Farm in Albert City, which killed two firefighters and injured six responders.

According to the report, the fire department arrived at 11:21 p.m. The initial report on arrival indicated that there was fire below the 3,785-litre LP propane tank and the tank was venting from the relief vents at the top of the vessel.

The fire chief indicated that the plan was to allow the fire to burn itself out and to protect exposures. As this strategy was being implemented, about six minutes after arrival, a tremendous explosion occurred, sending large sections of the LP tank flying in all directions.

The report says that the largest portion of the LP tank, a piece about 7.3 metres (24 feet) long, was hurtled more than 91.4 metres (300 feet). Another piece was propelled directly north, passing through the north building, and was stopped by a silo located more than 45 metres (150 feet) from the LP tank’s original location. A third large piece travelled northwest and struck two firefighters operating a hose line. The impact killed the two firefighters instantly. A piece of one of the vent pipes was found embedded about a metre deep into a gravel driveway more than 61 metres (200 feet) west of the LP tank’s original location.

According to the NFPA fire investigation, several significant factors directly contributed to the firefighter deaths:

- The close proximity of fire department operations to the LP tank while the tank was being exposed to direct flame contact.

- The lack of an adequate and reliable water supply in close proximity to the site to allow for sufficient hose streams to be rapidly placed in service to cool the LP gas tank that was being impinged upon by flames from the broken pipes.

- The decision to protect the exposed buildings and not relocate all personnel to a safe location given the fire impinging directly on the LP gas tank and the lack of a life hazard exposure.

Although not a BLEVE, the following report (which is widely available online) of an explosion in Buffalo, N.Y, is certainly an eye-opener regarding the power and unexpectedness of LP gas explosions. On the evening of Dec. 27, 1983, firefighters in Buffalo, N.Y., responded to a call regarding a propane gas leak. Shortly after arriving, the propane ignited, levelling a warehouse and causing a wide swath of damage. Five firefighters and two civilians were killed in the blast. This event remains the largest single-day loss of life for the Buffalo Fire Department (BFD).

According to several online reports, “Approximately 37 seconds after the chief announced his arrival, the tank exploded, instantly killing the five firefighters assigned to Ladder 5, as well as two civilians. The explosion injured approximately 60 other people, damaged a dozen city blocks and caused millions of dollars of damage in fire equipment. The force of the blast blew BFD Ladder 5’s tiller aerial 35 feet across the street into the front yard of a dwelling. BFD Engine 1’s pumper was also blown across the street with the captain and driver pinned in the cab. Engine 32’s engine was blown up against a warehouse across a side street and covered with rubble.”

It is vital that firefighters become familiar with the potential for a BLEVE. Empower them to make life-saving decisions regarding exposures and evacuations.

Key points to emphasize:

- Even a non-flammable liquid container can rupture.

- A flammable liquid can create a great fireball.

- Don’t assume that opening relief vents will prevent a BLEVE.

Although, at one time, it was thought fairly safe to be at the sides of an LP gas tank, it has now been noted that there are no safe sides of an LP gas tank.

The main hazards are fire, thermal radiation, blasts and projectiles.

Tests on a 400-litre propane tank (13 BLEVEs) showed projectiles travelling 200 metres (656 feet) from the ends of the tank and 125 metres (410 feet) from the sides.

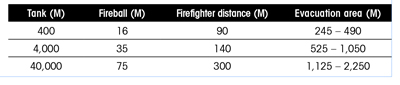

The following widely used table is a good safety guideline:

|

Time is the most important factor to consider. Containers can be in serious danger of experiencing a BLEVE after less than 10 minutes of intense flame impingement. There is no safe time period in which operations can be established. In the case of the Albert City incident, the BLEVE occurred about 18 minutes from the time the fire department was notified, and within eight minutes of the time the apparatus had arrived. In Buffalo’s tragic propane explosion, its members had 37 seconds!

The fire officer or firefighter has to consider whether to attempt to control vapours (when un-ignited gas is present), apply water to the container being exposed to flame, establish a safe evacuation area and allow the gas to burn off, or allow the BLEVE to occur.

The first instinct of firefighters may be to attack the fire or attempt to control escaping gas vapours. The incident commander (IC) must perform a risk-versus-benefit analysis of the situation. As difficult as it may be in many cases, the better course of action may be to retreat to a safe location and monitor the situation from a distance.

If a sufficient amount of water cannot be applied to the tank safely, then firefighters should be withdrawn to a safe, remote location, and the fire should be allowed to burn. In the case of train derailments or other large-scale incidents, a large hot zone should be established to reduce the exposure to fire forces and to the civilian population.

To prevent a container from exploding, firefighters must apply a steady stream of water with a minimum of 1,900 litres per minute (500 gallons per minute) at each point of flame impingement. This may not be possible in many rural areas, where firefighters have to rely on rural water supply operations.

The big decision that ICs need to address is whether to fight the LP gas fire or to retreat.

The potential dangers of BLEVE should be re-emphasized in your training. Look over the online resources and the lessons learned from these incidents. Honour our fallen brothers by using their line-of-duty deaths to help develop operational plans and procedures to guard against similar incidents.

Note that in each of these incidents:

- The relief valves were operating upon the fire department’s arrival.

- The weakened tank shells ruptured, sending tank pieces in all directions.

- The potential of a BLEVE was not given the utmost consideration.

Until next time, stay safe and remember to train like lives depend upon it, because they do.

online TRAINING resources:

- How it Happens Training Video BLEVE (Boiling Liquid Expanding Vapor Explosion) – www.youtube.com/watch?v=UM0jtD_OWLU

- NFPA: BLEVE (Boiling Liquid Expanding Vapor Explosion) – ncsp.tamu.edu/reports/NFPA/vapor_explosion.htm

- The Warwick Explosion: a Case Study – ncsp.tamu.edu/reports/IPR/warwick.htm

- Half An Hour To Tragedy: On Jan. 30, 2007, at 10:53 a.m., a propane explosion at the Little General Store in Ghent, W.V., killed four people and injured six. The dead included a fire department captain, an emergency medical technician from the Ghent Volunteer Fire Department and two propane-service technicians. The injured included two other Ghent Volunteer Fire Department emergency responders and four store employees who were inside the store at the time of the explosion. This incident was investigated by the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board; its findings were published in September 2008 – www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzdnUZReoLM

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., and Greenwood Fire and Rescue. The 21-year veteran of the fire service is also a fire warden with the B.C. Ministry of Forests, a Wildland Urban Interface fire suppression instructor/evaluator and a fire-service chaplain. Contact Ed at aka-opa@hotmail.com

Print this page