Features

Hot topics

Incident reports

Anatomy of a fatal fire

While some parts of this country were in a deep freeze for much of this winter, many of us in Central Ontario wondered if we would see winter at all.

April 4, 2012

By Brad Bigrigg

While some parts of this country were in a deep freeze for much of this winter, many of us in Central Ontario wondered if we would see winter at all. Indeed, some of us thought the milder temperatures and minimal snowfall might result in a marked reduction in the number of fatal fires.

|

|

| The first-arriving crew from Station 308 in Caledon found the residential structure well involved with smoke and heavy fire showing from all openings. Footprints in the snow led crews to believe there was a fatality. Photo courtesy Caledon Fire & Emergency Services

|

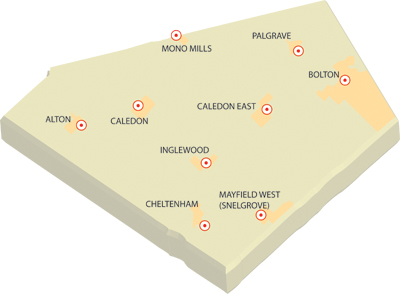

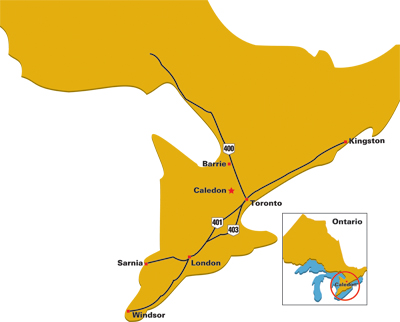

That wishful thinking didn’t last long for us in Caledon, Ont. On Sunday, Jan. 22, at about 8:44 a.m., the Peel Region Joint Fire Communications Centre received several 911 calls reporting a well-involved house fire on Calmon Drive in the Mono Mills fire district (Station #308). Mono Mills is one of nine settlement areas in Caledon with a small residential core surrounded by a larger rural area. This fire station also protects part of the adjoining Town of Mono. The Mono Mills station houses a squad, a pumper and a tanker. The station responded to 157 emergency incidents in 2011. A full-structure fire alarm (in a hydrant-protected area) was dispatched. This consisted of two rescue pumpers, (called squads in Peel Region), a pumper and a tanker.

As luck would have it, a crew of volunteer firefighters was in Station 308 carrying out duty-crew assignments when the pagers and printers were activated. Station 308 is less than a kilometre from the fire scene. The firefighters in the station observed heavy smoke conditions from the station, and made a help-call request for an additional pumper and tanker, primarily for additional firefighters. (A help call is the first step in calling for assistance in Ontario, not quite a second alarm or greater and not mutual aid)

First-arriving apparatus established water supply from two nearby hydrants. Command and several functional sectors were also quickly established. The initial size-up was a single family dwelling with one exposure on the Bravo side, well involved in fire with smoke and heavy fire showing from most openings. A defensive attack was initiated with 65-millimetre hoselines and two portable ground monitors until the fire was brought under control. The three major utilities – gas, hydro and water – were initially required at the scene to shut down utilities to support safe fire fighting operations.

While performing a 360 search of the perimeter of the home, firefighters realized that they had a serious problem: fresh snow had fallen overnight; there were fresh footprints leading into the home but none leading away from it. Forcible entry was made into the garage where the homeowner’s car was located. Command was advised that the home was most likely occupied at the time of the fire.

While firefighters from three stations attended this scene, command remained with officers from the home fire station. Command was supported by our division chief of operations and company officers from adjoining stations.

Due to the nature of this fire, I was notified early into the incident. I arrived some time after the fire had been benchmarked as under control. As I received a briefing from command and the operations chief, it was clear that they were well on their way to establishing operations and maintaining support for the long-term events required to determine if the home was actually occupied and the cause and origin of the fire.

It struck me at the time that this had been a strong firefighting operation and that all of the required functions had been carried out. It also struck me that our volunteer firefighters were going about their business knowing what needed to be done. But as I discussed the operation and control of the scene with some of our firefighters, it became clear that while they knew the what of the operation, they had many questions about the how and why. In most cases, I attributed this to a lack of experience due to a marked reduction in the number of fire fatalities over the past 30 years.

Here are some of the procedures associated with questions posed by our firefighters, in hopes that the details will help others in similar situations.

Notifications

1. Police service: Due to the nature of this incident, the first-arriving Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) constable was advised that we had a reasonable expectation that this would be a fatal fire. This triggered a number of functions. Once the fire was under control and hot spots were cooled, the OPP took custody of the scene and secured the site.

The police started a new crime scene accountability process, identifying every person who was present, or had been present, on the fire site during firefighting operations. Caledon Fire was able to quickly identify our volunteer firefighters on scene, as well as personnel from the gas, hydro and water.

The police service having jurisdiction carries out two roles in a circumstance such as this: it is responsible for investigating the occurrence to ensure that no criminal act has taken place; and it supports and assists the coroner in determining the circumstances surrounding a death.

Due to the expected length of this fire investigation, the OPP maintained a presence to secure the site overnight for the duration of the investigation in order to ensure that the scene was not altered.

2. Coroner: The coroner must be notified in the event of a death. If there is a fatality, any unnecessary fire-ground operations that may disrupt or contaminate the fire scene must stop until the coroner is contacted, attends the scene, makes the necessary enquiries and releases the body of the deceased to the police. Coroners have wide powers of entry, search and seizure.

Many of the coroner’s powers may be delegated to the police, who usually arrange for the removal of the deceased, at the coroner’s direction. The fire service, as a professional public unit of government, has a duty and a responsibility to assist and support the coroner throughout the investigation. This assistance may include the provision of statements, video or photographic evidence surrounding the incident, diagrams or drawings, help with the scene investigation, the collection of evidence at the scene, and the packaging and removal of the deceased if it is unsafe for police or funeral home staff to do so.

3. Fire investigator: The Office of the Fire Marshal (OFM) was notified of this fire once we realized there may have been a fatality. The OFM was also notified because this was a large-loss fire within the OFM investigative mandate. Most firefighting operations on the fire site – other than cooling hot spots – stopped until our fire prevention officer had spoken to the OFM fire investigator and received additional direction.

During this operational pause, time was taken to cycle volunteer firefighters through rehab, feed firefighters, return some apparatus to service, fill/rotate SCBA cylinders, and release non-essential volunteer firefighters and apparatus.

The pause also afforded every volunteer firefighter who attended this incident an opportunity to complete a Caledon Fire statement of initial actions. This report is completed during or as soon as possible following an incident in order to account for volunteer firefighter task assignments and time spent assigned to a fire.

Experience has shown that we receive the most complete and accurate information from our firefighters when they complete their statements immediately after an incident. The form also provides the OPP and OFM with some context concerning the incident when these agencies start their investigations.

During the investigation of the scene, the Electrical Safety Authority was required to attend, view, and comment on matters of electrical safety. The Technical Standards and Safety Authority also attended during the scene examination to view and comment on matters concerning the natural gas plumbing and function of the furnace system.

Logistics

The fire-prevention officer received guidance concerning initial management of the fire investigation scene over the phone from the OFM fire investigator. It was clear that the examination of this scene would take a number of days. Several support functions had to be put in place to ensure that this fire-investigation process continued to move forward without stalling due to a lack of support or resources. One Fire & Emergency Services administrative assistant was brought in to ensure that the necessary logistical support was in place for the activities required for the following day. The administrative assistant was also responsible for the collection of each Caledon Fire statement of initial actions and all invoices for extraordinary costs associated with fire fighting.

|

|

| Several steps had to be taken to preserve the scene for the coroner; efforts were hampered by snow and freezing rain but having a protocol in place for a fatal fire helps crews operate more efficiently. Photo courtesy Caledon Fire & Emergency Services

|

The logistics required to support a fire-scene examination included the scheduling of volunteer firefighters and fire-prevention staff to support the scene examination, heavy equipment to remove debris, portable pumps to remove water used for fire fighting, shelter, rehab and feeding, spare/dry protective clothing, and assistance from the OPP to secure the site when it was not being actively investigated.

During the day of the fire, initial actions were taken to prepare the property for a scene investigation. Heavy equipment was brought to the site as there was significant structural collapse. The heavy equipment was used for four days to make the structure safe under the direction of the OFM fire investigator, and to remove debris as directed. Caledon firefighters removed some debris from the scene by hand as directed. Work at the scene ceased at sunset. Portions of the site were covered with poly-tarps. The fire scene was secured by an OPP officer.

Day 2

We experienced winter the following morning with temperatures below zero, moderate winds and freezing rain, sleet and snow. At about 8:40 on the morning following the fire, Caledon fire-prevention officers and volunteer firefighters attended the scene to support the OFM fire investigator. Equipment used on the scene for the duration of the scene investigation consisted of one in-service rescue/pumper, the Caledon Fire command post, and two admin vehicles, along with the fire investigator’s vehicle. Heavy equipment was on scene to assist with the removal of debris during the scene investigation.

Fire investigators used a systematic approach to investigate the scene, from the least affected area working inward toward the potential area of origin. This involved the use of hand tools such as shovels, brooms, trowels and rakes to remove debris with painstaking attention to detail. A portable pump was required to remove water used for fire fighting from the basement of the structure.

During the mid-afternoon of Day 2, remains were found in the basement of the home. All site work stopped, volunteer firefighters were removed from the residence and the OPP notified the coroner’s office. The coroner arrived on the scene about an hour later.

The coroner determined that the remains were human and the identity was unknown. Two hours later, the remains were removed to the chief coroner’s office in Toronto for post-mortem examination. The work for Day 2 was completed following removal of the deceased. The police again secured the scene overnight pending additional scene investigation.

Days 3, 4 and 5

On each of these days, Caledon fire-prevention officers and volunteer firefighters attended the scene to support the OFM fire investigator as requested. Depending on direction and OFM caseload, work started and stopped in accordance with direction, circumstances and available sunlight.

At noon on Day 5, the investigation of the scene was completed. Volunteer firefighters were decontaminated, PPE was inspected and sent for cleaning or was replaced as necessary. Fire-department equipment was cleaned, maintenance was performed and firefighters, equipment and apparatuses were returned to service. All members completed the necessary reports prior to leaving their stations for the day. All invoices were collected and fire-department costs were calculated in order to invoice the fire insurance company accordingly.

Lessons learned

Caledon firefighters had faced a similar incident involving a homicide and total-loss residential fire 11 months earlier. Lessons learned from that fire included the need to prepare for a long-term scene investigation. The following steps were adopted:

- Notify the police and fire investigator as soon as possible: this allows them to mobilize and prevents the need for volunteer firefighters to hurry up and wait for investigators to get their plan in place. Release volunteer firefighters who are not required at the scene as soon as possible.

- Ensure that firefighter statements or reports are completed at the scene or as soon as possible. This ensures that the most accurate information is documented shortly after the incident and eliminates the need for the police to try to track down firefighters following the incident.

- When a fire fatality is anticipated, assign an officer to longer-term planning. It was clear that the scene investigation of this fire would take more than a day or two. Past experience has shown that where a fatality is anticipated, the investigation of the scene may take three or more days. The planning officer started to prepare a plan for coverage of the fire district that ensured a number of volunteer firefighters were available to support the fire investigation.

- Thankfully, fires of this magnitude are becoming less common. Since we infrequently deal with these types of incidents, it was helpful to have an administrative assistant on scene to manage the preparation of the necessary statements and reports, maintain financial records for services purchased such as food and heavy equipment, and ensure that a logistics chain was in place when we required external services or equipment. This allowed command to focus on the immediate operational needs.

- Ensure that firefighters receive rehab and are rotated regularly during the fire operation and the scene examination. In our situation, command and company officers did a great job ensuring that firefighters went through rehab as required. I tend to think that we could have done a better job of rotating people off of the scene once we achieved loss stopped. Many volunteer firefighters remained on the scene for close to 10 hours. This was probably unnecessary as much of the time in the afternoon was spent awaiting investigative direction.

Profile – Caledon Fire & Emergency Services |

Brad Bigrigg has served in public safety throughout Ontario for almost 35 years, as a police officer, volunteer chief fire officer, assistant fire chief responsible for fire and EMS operations, and emergency manager for the Ontario Office of the Fire Marshal. He is currently the fire chief for Caledon Fire & Emergency Services. Brad is also an associate instructor for the Ontario Fire College and Emergency Management Ontario. E-mail him at brad.bigrigg@caledon.ca

Print this page