Features

Hot topics

Labour relations

The politics of platooning

Like similar-sized communities across Canada, the picturesque town of Caledon, Ont., has a composite fire department and many of its 65,000 residents know each other and the fire chief.

March 15, 2010

By

Laura King

Like similar-sized communities across Canada, the picturesque town of Caledon, Ont., has a composite fire department and many of its 65,000 residents know each other and the fire chief.

That small-town connectedness is how Caledon councillors learned about concerns that some volunteer firefighters were getting called out to too many minor incidents – false alarms, CO calls and medicals – and were starting to tire of the disruptions in work, sleep and routine.

|

|

|

Caledon Fire & Emergency Services Chief Brad Bigrigg was asked to find a solution to the perceived burnout and on March 1, 2009, the department instituted a pilot program under which only some firefighters would be paged out to certain CO and medical calls. The aim of the platooning project was to determine if the municipality could call fewer firefighters to some incidents and maintain an adequate level of service.

Essentially, the trial added more than two minutes to Caledon Fire & Emergency Services response times due to traffic and infrastructure issues and Caledon has since returned to its original paging and dispatch protocols.

In a December report to council, Bigrigg bluntly concluded that platooning might work in some suburban areas but it is not a good system for his community right now, primarily because of logistics and station locations.

But alternative deployment models could indeed become the norm for Canadian fire departments because of the changing nature of the fire service.

Over the past two decades the number of emergency calls has increased considerably and the variety of emergency services provided has expanded. Fire departments are also facing challenges recruiting and retaining volunteer firefighters. This had led some fire service leaders to ask whether departments are overworking the volunteer firefighters they have.

Operational systems in North American fire services are organized around responses to structural fires. But with more than 80 per cent of calls for medical incidents and MVAs, the longstanding system of paging out a full contingent of volunteer firefighters for all calls may not make sense, says Barry Malmsten, executive director of the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs.

“What business gears 100 per cent of its operational staffing and equipment deployment protocols based on five per cent of its business needs?” he asks.

Fire departments must be equipped and staffed to deal with fires. But most calls are not for fires, so is it necessary to deploy a full fire response to other incidents? If departments deploy too many volunteer firefighters to calls for which they are not needed, will the firefighters become frustrated with the constant interruptions to their personal lives and resign? How do departments maintain response times and deploy only the appropriate number of firefighters for the incident? How do they build flexibility into the system? This was the challenge for Caledon.

|

|

|

click here for larger image

|

■ Caldeon’s case

Nestled northwest of Toronto and famous for its undulating hills, Caledon employs a full-time chief, deputy chief, fire prevention officer, inspector, public education officer, two training officers, three administrative assistants, three captains, 11 full-time firefighters and 245 volunteers at nine stations that protect 270 square miles. It has 11 pumpers, one pumper/aerial, eight pumper squads, seven pumper tankers, two water tankers and one command/lighting unit. Caledon Fire & Emergency responds to about 2,200 calls a year. Three stations were involved in the platooning project – Snelgrove, Bolton and Palgrave.

In his report, Chief Bigrigg said a number of options to help reduce the perceived strain on volunteer firefighters were considered including scheduling, implementation of duty crews, paying only those who attend an emergency scene and platooning. After consulting with firefighters and other Ontario chiefs, the platoon system was determined to be the most advantageous and least disruptive option.

Under the platooning system, about 65 per cent of the participating stations’ volunteer firefighter strength was paged for medical emergencies and carbon monoxide alarms where no medical symptoms were present. Generally, Bigrigg said, the system would page between 12 and 18 volunteer firefighters per station between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m. during the business week.

“It was hoped that there would be sufficient volunteer firefighters available to maintain adequate staffing, response times and response capabilities without the need to page all volunteer firefighters from the participating fire station,” Bigrigg said.

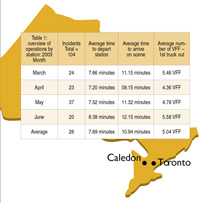

The table from Bigrigg’s report shows the average depart-station and arrive-scene times for the test period. Incidents analyzed during this period were medical emergencies and carbon monoxide detectors activated with no medical symptoms only. Of the 104 emergency incidents where the platoon system was used during the pilot project period:

- 14 (13.4 per cent) incidents had a depart station time of less than five minutes, which is the standard expectation for volunteer fire stations.

- 90 (86.6 per cent) incidents had a depart station time greater than five minutes. This triggered the paging of an additional platoon or neighbouring fire station, which is the industry norm.

- 29 (27.8 per cent) incidents had and arrive scene time of less than 10 minutes, which is the standard expectation for volunteer fire stations.

- 57 (54.8 per cent) emergency incidents had an arrive scene time greater than 10 minutes.

- 18 (17.3 per cent) emergency incidents were cancelled by EMS either because EMS was already on scene or EMS was departing the scene and fire was not required.

|

|

| click here for larger image

|

According to Bigrigg’s report, the average depart-station time for Caledon in 2008 was 5.45 minutes. The average arrive scene time in 2008 was 8.67 minutes. Project data shows the depart-station times were about 2.5 minutes greater than the average 2008 times and the arrive-scene times were about 2.3 minutes greater than the average times.

In many cases, Bigrigg said, the assembly time for an adequate fire crew at the station caused a delay in the overall arrive-scene times.

“The overall arrive-scene times are critical to the nature and quality of the response provided by Caledon Fire & Emergency Services,” the chief said. “While there was no public concern expressed regarding an increase in response times there were concerns raised by both fire and EMS personnel.”

In addition, Bigrigg said, the medical director of the Base Hospital Program reviewed the data and expressed concern about the increase in response time. And, he said, the Office of the Fire Marshal was concerned that the longer response times could be viewed as a reduction in a previously established level of service.

Caledon, Bigrigg said, faced some unique challenges that impacted the success of the program, including:

- The amount of traffic congestion, the number of controlled intersections and the number of traffic signals in the Bolton Fire District. It simply takes a long time for responding volunteer firefighters to travel to the Bolton station.

- The limited number of volunteer firefighters in each fire station. The fire stations were designed for a limited number of volunteer firefighters and are too small to house additional PPE.

- The amount of time and the time of day that volunteer firefighters spend travelling to and from their workplaces outside the municipality.

- The limited amount of free time that volunteer firefighters actually have.

- The amount of time that volunteer firefighters spend outside the community.

Financially, Bigrigg said, there were no salary savings during the platooning project. The purchase of 90 additional pagers was included in the approved 2009 capital budget and there was no impact on the capital or operating budgets.

Bigrigg warned council that the increase in response times could put the municipality at risk for civil liability if a slower response time created a serious risk of life-threatening injuries.

■ The background

Bigrigg spoke to the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs conference about platooning in April 2008, shortly after the pilot project got underway.

“I was doing this because I was directed to do so. It was assigned work and something that I felt that we should try,” Bigrigg told the OAFC. “I am not a proponent or a detractor of platooning; I was carrying out assigned work.”

Admittedly, Bigrigg said, Caledon was sending between 25 and 30 firefighters to most calls. “Ultimately,” he said “we were trying to put the right number of firefighters on responses and provide good protection to the people of Caledon.

“Word around town was the volunteer firefighters were too busy; that there were too many nonessential calls and too many volunteer firefighters standing around.

“Nobody had come to me and said ‘We’re stressed out and doing too much’. It was the firefighters talking to councillors and neighbours at the grocery store and telling them they’re going to CO calls . . . and councillors decided to address this at council.”

Bigrigg is a straight-talking chief with a stellar reputation but his firefighters were skeptical about the platooning project.

“When I went to stations to talk about this, the immediate response was that it was just a cost-cutting remedy,” he said. “I don’t believe that was true – salaries for volunteer firefighters were increased by $150K [in 2008] – this was trying to help the firefighters.”

|

|

|

|

Bigrigg and his chief officers had to choose three stations to test the platooning system – one urban, one suburban and one rural. Caledon’s district chiefs then determined which volunteer firefighters would be in each platoon.

For Bigrigg, the most frustrating part of the pilot project was the skepticism by firefighters about management’s intentions and the belief that platooning was simply a way to cut their pay. Some firefighters, he said, didn’t understand that management was under a directive to try to improve what was perceived to be a difficult situation for volunteer firefighters who were getting called out too often.

Indeed, there was talk among firefighters of a boycott – of not responding to pages – but in the end everybody tried to make the system work, Bigrigg said.

Interestingly, he said, there was no public feedback on the platooning system despite several stories in the local newspaper about the new system.

Bigrigg said he believes a platoon system can work in a suburban area but that Caledon needs infrastructure changes, specifically the scheduled relocation of one station, for a platooning system to be effective.

Overall, he said, the aim of the platooning project was to reduce stress on volunteer firefighters and his concern now is to make sure that happens.

“If our original concern was that our volunteer firefighters are wearing down, and if the pilot didn’t work, are we doing something else?”

Bigrigg says that while the platooning wasn’t right for his department under the present circumstances, initiatives over the last year have had a significant impact on the volunteers, including improved triaging of calls by EMS, better management of call volume and a widening of the coverage area of the career staff at the Bolton station, which has reduced the number of page outs for volunteers.

■ What’s ahead

Malmsten expects an operational sea change in the fire service in the next 10 to 15 years but says it won’t happen until departments like Caledon experiment with potential new systems, determine what works and what doesn’t, and then share their findings.

Print this page