News

Pandemic preparedness

CURRENT ISSUE

CURRENT ISSUE

Pandemic preparedness

For months, fire departments across Canada have taken the H1N1 threat seriously and developed plans, procedures and supply strategies to cope with potential worst-case scenarios.

November 6, 2009

By James Careless

Nov. 6, 2009 – For months, fire departments across Canada have taken the H1N1 threat seriously and developed plans, procedures and supply strategies to cope with potential worst-case scenarios.

“We have a pandemic response plan which escalates our response activities as the risk goes up,” said Dave Meldrum, divisional chief of Halifax Regional Fire & Emergency’s

safety division.

|

|

|

|

“Right now, we are at a relatively low alert level but if the disease becomes more widespread and/or more lethal, some of the additional measures we can take include restrictions on the type of calls we respond to – no Influenza-like illness (ILI) medical calls, for example – restrictions on meetings and training events, lock down of our stations to prevent entry of any persons other than working firefighters, and pre-entry symptom screening of firefighters

before they are allowed to start duty.”

Dan Heney, deputy chief with Prince Albert Fire & Emergency Services in Saskatchewan said all risks of this magnitude are handled similarly: educate on the potentials and establish contingency plans for the worst.

“Health professionals have suggested all hazards pandemic plans be generated for sometime now, but legislators seemed to only advocate planning for specific events,” he said.

In some instances, departments were able to draw on past planning to prepare for H1N1. “We had to do all of this before for SARS in 2003,” says Joe Kowal, the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service’s emergency medical services liaison with the regional health authority.

“Although we were fortunate in not having to deal with SARS like our Toronto colleagues had to, the thinking that went into the SARS plan works equally well for coping with H1N1.”

|

|

| Fire departments across the country have been working for months on pandemic preparedness plans to ensure the firefighters and paramedics are protected from the H1N1 virus

|

H1N1 plans run the gamut from educating firefighters to protect themselves against infection and minimizing exposure to infected patients to deciding what supplies need to be available on trucks and in stations.

In the case of the Fredericton Fire Department in New Brunswick, pandemic planning goes beyond prevention and protection to an investigation to determine how to keep the department running on reduced strength. FDD also examined how its personnel might be cross trained to help with other city services, said Assistant Deputy Chief Paul Fleming of the department’s prevention and investigation division.

“This could include personnel with heavy equipment licenses, experience with chain saws and so forth,” he said.

Deputy Chief Dale McLean of Edmonton’s Fire Rescue Services said education is central to Canadian fire departments’ preventative approach to H1N1.

“We are telling our staff to follow the universal precautions for protecting themselves from infection, such as hand washing and using proper masks, gloves and gowns when responding to potential infection calls,” he said. “We are also teaching them to know what the symptoms of H1N1 are, and that they should stay home should they show any of these symptoms personally.”

In B.C., Port Coquitlam Fire & Emergency Services has worked with provincial agencies to develop a self-guided PowerPoint presentation on H1N1, said Fire Chief Stephen Gamble.

“It goes through the dos, don’ts and best practices for dealing with H1N1, and viewing it is a required part of each employee’s training regime.”

In Winnipeg, the city has created a website on its intranet where information is shared with staff, said Randy Hull, Winnipeg’s emergency preparedness co-ordinator.

“We have 10 separate H1N1 bulletins posted for staff. We have also held refresher courses on the proper usage and deployment of respirator masks and gloves.”

With 84 halls and 3,000-plus employees, Toronto Fire Services can’t address the H1N1 challenge by having “a tailgate education program,” said Capt. Tim Metcalfe, an occupational health and safety officer. So the department has sent out information through its regular fire chief communiqués via the TFS intranet.

“They talk about ways of protecting yourself and include fact sheets about immunization and H1N1. Our union is also posting information on their website.”

After education, sanitization is the next step in the fight against H1N1.

“We have hand washing stations and hand sanitizer stations at all work locations,” says Halifax Divisional Chief Dave Meldrum. “We have hand sanitizer stations installed on all apparatus and we have completed quantitative fit testing on all career firefighters for their N95 respirators and are starting on our volunteers now,” he said.

|

|

|

Photo by The Canadian Press

|

Properly fitted N95 respirators, protective gloves and gowns for use in ILI situations have become standard equipment at many Canadian fire departments, in their stations and on their apparatus.

“Our people already are equipped with these items on their trucks,” said Brent Denny, deputy chief of volunteers for the Cape Breton Regional Fire Service, which oversees 33 fire departments – three professional, three professional/volunteer and the rest volunteer.

“Meanwhile, we have added an extra layer of protection by having our emergency health service dispatchers ask callers whether people have flu-like symptoms in their households. This allows us to give our people advance warning when they may be entering ILI situations.”

Toronto Fire Services’ dispatchers also alert its officers about possible exposure risks during calls. When a risk is present, TFS personnel follow routine precautions for dealing with infectious diseases, says Capt. Metcalfe. This means wearing bunker gear and boots, eye protection, protective nitro gloves and fitted N95 respiratory masks. The department does have gowns in stock, “but we haven’t received direction from the base hospital to start wearing gowns,” he said.

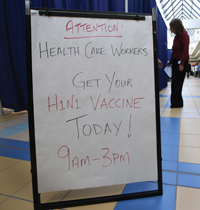

Canadian fire departments appear united in their attitudes towards H1N1 vaccinations: they want personnel to get vaccinated but they want the decision to be voluntary. The hope is that education will motivate firefighters to get the H1N1 shots.

“Our people are being strongly encouraged to get the H1N1 shot,” said Edmonton’s Dale McLean.

In Prince Albert, emergency responders were on the region’s priority list, said Dan Heney. “When our priority level is reached, we will be vaccinated.”

Toronto Fire Services also took the voluntary vaccination approach, but in an effort to save time it brought vaccination clinics directly to firefighters. “The immunizations are being performed by EMS paramedics and Toronto Public Health nurses,” said Capt. Metcalfe. The program was part of a city-wide effort to protect tier-one workers, including public safety officers and workers at seniors’ homes.

At press time it was unclear how severe the H1N1 infection would be. Regardless, the more people who get sick, the higher the danger to firefighters of exposure to H1N1 at work and at home. The real danger was that substantial numbers of firefighters could be lost to duty due to sickness, reducing departments’ ability to cope with daily duties.

Editor’s note: Research for this story was done in mid- October, before the H1N1 virus began to spread in late October.

| First responders question vaccine hierarchy

At press time in early November, while thousands of school children were absent from classes across the country due to flu symptoms, it was too soon to determine the impact of the H1N1 outbreak on first responders or any other group, but fire officials in some provinces were clearly frustrated that their personnel were not included in the vaccination priority group. Most Canadian fire departments had been working for months on pandemic plans for their own personnel and for their communities and were disappointed when their members were not among the first to receive vaccinations. Start dates for vaccine programs varied from province to province although the recipient order – people under 65 with chronic illnesses, seniors, pregnant women, young children – was fairly consistent across the country. Most provinces included health care professionals in the first group to receive H1N1 shots in late October but medical first responders were listed in the priority group only in some jurisdictions, including B.C., Manitoba and Quebec. In Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, medical first responders started getting their shots the first week of November, well after the virus had started to spread. In Alberta, Lethbridge firefighters could get their shots at a special clinic at the local hospital on Oct. 29 but establishing the clinic took considerable effort by fire officials. Kitchener, Ont., Fire Chief Tim Beckett, who is the first vice-president of the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs, was quoted in a firechief.com story in October explaining to U.S. readers that the Ontario Ministry of Health had identified the order in which people were to receive the vaccine. “We don’t fall under the health care workers,” Beckett said of medical first responders in Ontario. “First responders fall under phase two.” In Toronto, firefighters were able to get the vaccine in the last week of October through a clinic aimed at protecting tier-one workers. At press time, most Canadian communities had just begun to vaccinate the general public and first responders. While the vaccine wasn’t available in Canada until late October, many U.S. first responders were vaccinated in early October. Becket said in an Oct. 28 interview that fire officials hope to work with the province to establish a new protocol for first responders for any potential future pandemics or similar situations.

By Laura King

Photo by The Canadian Press

|

Print this page

When the second wave of H1N1 virus struck in late October killing a 13-year-old Toronto boy, the vaccine was just being rolled out and Canada’s first responders hadn’t yet been vaccinated.

When the second wave of H1N1 virus struck in late October killing a 13-year-old Toronto boy, the vaccine was just being rolled out and Canada’s first responders hadn’t yet been vaccinated.