Features

Hot topics

Incident reports

Six alarms: Toronto battles historic blaze

Just eight weeks after fires destroyed historic properties in Wasaga

Beach and Barrie, Ont., a massive, six-alarm blaze tore through a block

of Toronto’s Queen Street on Feb. 20, challenging firefighters and

testing the limits of the Toronto Fire Service’s incident management

system.

April 9, 2008

By

Laura King

Just eight weeks after fires destroyed historic properties in Wasaga Beach and Barrie, Ont., a massive, six-alarm blaze tore through a block of Toronto’s Queen Street on Feb. 20, challenging firefighters and testing the limits of the Toronto Fire Service’s incident management system.

“The biggest lesson we learned,” says Toronto Fire Commander Andrew Kostiuk is that we need to improve our IMS training.”

|

|

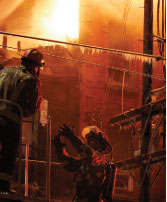

| PHOTOS BY JOHN HANLEY AND KEITH HAMILTON Toronto photographers John Hanley and Keith Hamilton were on scene and captured the path of the Feb. 20 blaze that destroyed a block of history on Queen Street in Toronto, the aftermath of the blaze and the gruelling work in the freezing temperatures. |

|

The speed at which the fire consumed the tinder-dry block of storefronts and apartments made it difficult for officers to keep up.

“We noticed that we had to get our command post up and running faster to keep up with a fast-moving fire like that,” Kostiuk said. “We were playing a little bit of catch up.”

In the aftermath of one of the biggest fires in Toronto’s history, Kostiuk said fire officials are also considering how to improve communication with sector officers who were stationed at various points around the block. Other officers couldn’t get to the sector officers without walking around the buildings, losing valuable time. Kostiuk said radio communication needs to improve so that information can be shared faster.

More than 130 firefighters were on scene as the fire enveloped decades-old family owned shops and second- and third-storey flats. Toronto Fire Services responded to the call at 5:06 a.m. with between 34 and 56 of the department’s 130 apparatus on scene at any given time. The last firefighters left the scene three days later, on Feb. 24 at 7 p.m., but some firefighters helped with the investigation through Feb. 29. Access to that particular section of Queen Street was difficult because of narrow laneways behind the buildings.

The fire left 20 people without homes but there were no injuries. Still, Toronto Fire Services and the Toronto Police Service were bombarded with calls from worried family members. The delicacy of dealing with frantic relatives and ensuring that accurate information is disseminated is another area that Kostiuk says has been targeted for improvement.

“People were calling in from all over the country looking for their loved ones so we’re looking at doing some work around having a phone number that people can call,” he said. “That’s one of the issues that would lighten the load on the police too.”

For Capt. Adrian Ratushniak, an information office with Toronto Fire Services and a firefighter for 19 years, the Queen Street blaze was among the most remarkable of his lengthy career.

“It’s certainly a day that will be entrenched in my memory forever,” he said, still marveling at the speed at which the fire moved through the buildings and the impact of the blaze on landlords, tenants, businesses, area residents, commuters, the Toronto Transit Commission and firefighters.

Unlike the blaze in Wasaga Beach on Nov. 30 that was whipped by extremely high winds, there were light winds the morning of the Toronto fire but temperatures had dipped by 7 a.m. to -11 C with a wind chill of -21 C.

“Water and mist and spray was landing on the firefighters and creating icy bunker suits,” Ratushniak said, “so it made our suits crinkle and crunch as we bent or arms and keens, and the surface below you was pure ice.” The firefighters’ collective agreement stipulates that crews spend no more than four hours at a time at a fire and fire watches were rotated every two hours. Those on scene were rotated as needed to the canteen to rehydrate and warm up.

Flames, smoke and fog caused by the combination of fire and water reduced visibility on Queen Street and that made it difficult for some firefighters in the defensive, surround-and-drown position at street level to determine how the fire was moving, Ratushniak said.

|

|

|

|

“It was very dark,” he said. “The power on the street was disconnected so we were basically working in darkness with the exception of the lighting that we provide. Basically, the flames were visible from the tops of the buildings and lit up the sky but there were periods where it was soup-like thick fog that descended down on us – we’d hit something with the hoses and it would turn to steam and it would lay low.”

Ratushniak was in front of landmark retailer Duke’s Cycle, at the west end of the Queen Street block, when the fire jumped to that building from the one immediately to the east. Within minutes, the 94-year-old building collapsed.

“Nobody anticipated that,” Ratushniak said of how quickly the building came down. “Through training we understand building design and the building collapsed inward, as it was designed to do in 1800s, so it crumbled inward and caused no danger to firefighters.”

The pace of the fire meant that the mostly wooden buildings – one of the structures was built in 1868 – were being consumed faster than firefighters could douse them with

water.

“Until the roof caves in you have limited access to the fire,” Ratushniak said. “When you have a fire spreading so rapidly and the wood being so old that it’s just being consumed at a rate far faster than we could supply the water to put it out . . . We had numerous water towers et up spraying the water down. It’s difficult to watch something of such historical value and a landmark go up.”

Toronto Fire Services received the first call for the Queen Street blaze at 5:06 a.m. By 6:24 a.m. – just an hour and 18 minutes later – the fire had become a six-alarm, one of only a handful of six alarms in recent memory, says Commander Kostiuk, who responded to the fifth alarm.

|

|

The Queen Street fire ranks among the largest in Toronto, along with a seven-alarm blaze in October 2006 at a century-old paint store – also on Queen Street – a six-alarm fire at a plastics plant in March 2005 and a five-alarm blaze at the New York Pork and Meat Exchange in August 2006.

The partial collapse of family owned Duke’s Cyle at about 7:15 a.m. created a natural fire break that assisted firefighters to contain the blaze, Kostiuk said.

Like any other event in a major city, the impact of the Queen Street fire was felt by hundreds of thousands of people. In addition to the emotional impact on the 20 residents and the surrounding Queen Street community, the fire shut down one of the city’s busiest transit routes. Streetcars that usually run along Queen Street were diverted for almost two weeks during an already brutal winter for commuters.

The displaced residents had a particularly tough time after the fire, watching heavy equipment tear through their belongings, some of which appeared salvageable. A report of potential asbestos meant that residents couldn’t go near the rubble and that investigators had to wear light, Tyvek hazmat suits despite the freezing temperatures.

The cause of the fire hadn’t been determined at press time.

Print this page

Advertisement

- Defibrillator training program debuts in Canada

- TERC challenge tests extrication specialists: Teams encouraged to compete in regional events