News

State of emergency?

CURRENT ISSUE

State of emergency?

Survey reveals aging equipment, inadequate budgets and disparities between career and volunteer departments, but not all departments have the same needs. Experts sound off on the survey results in our March cover story.

February 25, 2009

By

Laura King

|

Editor’s note

In September, we asked you to help us help the fire service make its case for more funding for training, apparatus, personal protective equipment and public education.

We based our country-wide survey of fire departments on what we thought we knew – that equipment is out of date, that volunteer recruitment and retention is a challenge, that training in volunteer departments is an overwhelming task that sometimes doesn’t get done properly, and that public education gets short shrift in the budget.

We were right.

Now, it’s time for next steps.

The story below summarizes the survey results, the reactions of fire officials from coast to coast and their suggestions for action to correct budget inequities and other challenges. For another take on the survey, turn to Peter Sells’ Flashpoint column on page 46. To see the survey results, go to ww.firefightingincanada.com. And for a list of the winners of our survey contest, see page 4 or go to www.firefightingincanada.com.

Lastly, we’d like your input on the survey results and your thoughts on proposed solutions to the challenges of training, funding, aging equipment and volunteer recruitment and retention. E-mail us at lking@annexweb.com. We’ll post your thoughts on our website and in our May issue.

|

|

| FFIC’s national survey of fire departments found that large percentages of fire service equipment – bunker gear, SCBA and apparatus – are older than recommended by the NFPA; in some departments, all bunker gear is more than 10 years old. |

Are Canada’s fire services in a state of emergency? If you’re a glass-half-full person you might interpret our survey results this way: two-thirds of departments have high-tech thermal imaging cameras; most firefighters at a scene carry a radio to communicate with each other; and all departments have working apparatus suitable for their municipalities. Sounds good, right?

But if you’re a glass-half-empty thinker you’d see the data like this: apparatus, bunker suits and SCBA are getting old and unsafe; the average budget for public education is less than the cost of a week’s worth of fire-hall groceries; one-third of departments don’t have TICs; and training volunteer firefighters to appropriate standards is like trying to convince the Ontario government of the need for mandatory residential sprinklers – darned near impossible.

State of emergency? Most of the fire officials with whom we shared our data in February agreed that Canadian fire services are underfunded, undertrained undervalued and accustomed to making do with aging equipment and strained resources rather than operating at optimum levels of safety and performance. Somebody call 911.

| Survey stats | |

| A four-page survey was designed jointly by Fire Fighting in Canada and Readex Research. The survey was bound into 5,300 copies of the September 2008 issue of Fire Fighting in Canada. Data was collected via mail, fax and electronic survey from Sept. 19 to Dec. 10. The survey was closed for tabulation with 490 usable responses, a nine per cent response rate. The margin of error for percentages is ±4.2 per cent at the 95 per cent confidence level. That is, 95 per cent of the time we can be confident that percentages in the actual population would not vary by more than this in either direction. |

■ The big picture

Clearly, from the 490 responses to our survey (most of which were from volunteer departments) many volunteer departments operate on shoe-string budgets with aging equipment and apparatus, no time and little money to train and less funding for public education than Stephen Harper spends on a suit.

Not only that, the survey results show that although more than half (53.3 per cent) of firefighters are under 40 years old, the other half (46.3 per cent) – you guessed it – are over 40. Once again, it depends how you look at it but there’s no question that Baby Boomers are retiring and many departments are having trouble with recruitment and retention.

“If you take these numbers and factor in the number of departments that are not full time (in other words, rural), you might see that there is a crisis brewing in recruiting firefighters in smaller rural departments,” says Randy Vilneff, training officer at the 27-member Marmora and Lake Fire Department in Ontario, about half way between Ottawa and Toronto.

Bernie Turpin, a district chief with Halifax Regional Fire and Emergency Service and president of the Maritime Association of Fire Chiefs agrees: “The large number of Baby Boomers retiring from the career departments has made openings for new blood in the career departments, thus lowering these averages. [But] in small rural departments, like my old one in Blandford, the average age is over 50 years.”

■ Aging apparatus

As expected, the survey results show that more than one in three fire trucks in use today was built more than 15 years ago. That’s before 1994 – before free trade, before the Lillehammer Olympics. Seems like a long time ago, doesn’t it?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

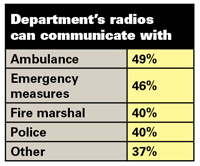

| base: 490 respondents (multiple answers) *“other” includes mutual aid partners, other fire departments, dispatch, public works, each other/base, DNR, and any other mention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“This not only creates problems in servicing the trucks,” Vilneff says, “but also in them being up to standard with regards to safety features, lighting (strobes, flashers and scene) and pump capacity.”

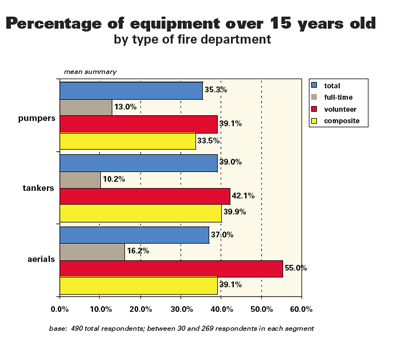

According to the data, 20 per cent of volunteer departments said all their pumpers are more than 15 years old, 22 per cent said all their tankers are more than 15 years old and four per cent said all their aerials are more than 15 years old.

By contrast, no full-time departments have pumpers over 15 years old; all pumpers and tankers at three per cent of full time departments are more than 15 years old.

Bruce Whitehouse, president of WHITING Canada in Burlington, Ont., parent of roll-up door maker Amdor Inc., looks at the results from a manufacturing point of view, noting that if aging apparatus are not replaced now, in five years almost 40 per cent of equipment will be more than 20 years old and replacement costs will be even higher.

“The process to spec and build apparatus can take many months – for some larger and more complex pieces it can take well over a year. We can’t just decide to take action today and take delivery tomorrow. It is time to fix the fleet issues before they become a problem that is too big to deal with.”

According to the survey, more than 80 per cent of departments have between one and four pumpers; 72 per cent have between one and four tankers and 27 per cent have between one and four aerials. This appears to be an accurate reflection of the fact that rural departments don’t need aerials and urban departments don’t need tankers.

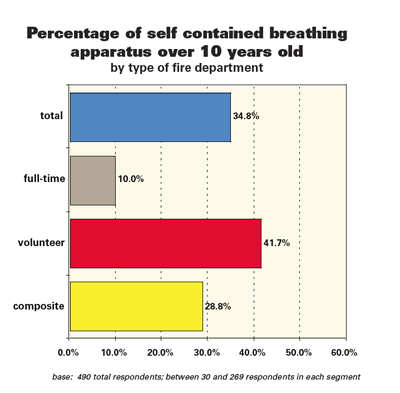

■ PPE

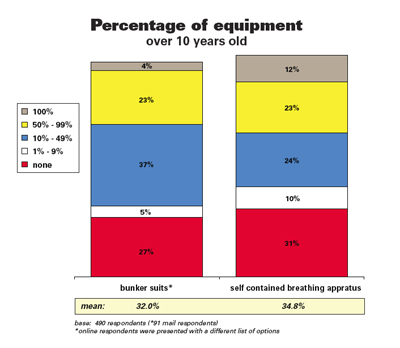

On average, according to the survey, 32 per cent of bunker suits and 35 per cent of SCBA are more than 10 years old. What’s more, 12 per cent of departments indicated that all of their SCBA are older than 10 years.

According to the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs, there have been on average 28,569 fires a year in the province over the seven years between 2001 and 2008, resulting in 101 deaths, 862 injuries and almost $414.3 million in property damage.

In its February 2008 submission to the Ontario Liberal government, the OAFC said these numbers show that fire is deadlier than all natural disasters combined, yet funding for the increased demands on fire department has not kept pace.

The OAFC’s own 2008 survey indicated that 42 per cent of all fire vehicles in Ontario are over 15 years old, 17 per cent of all firefighter bunker suits are over 10 years old, 22 per cent of all self-contained breathing apparatus units are over 10 years old and only 12 per cent of departments have radios that are capable of communicating with police and ambulance during emergencies.

“This aging equipment does not meet industry standards, and the insurance industry would find equipment of this age suspect,” OAFC president Richard Boyes said. “We’re worried that the equipment may fail when it is needed most.

Vilneff, whose department is volunteer / paid on-call, is a glass half-full kind of guy: “Reverse the stated age percentages [in the FFIC survey] and you discover that two-thirds of all gear and SCBA are under 10 years old,” he says. “This is probably the best statistic in the report. Perhaps it shows a serious commitment to personal protection.”

Halifax’s Bernie Turpin, whose sprawling, regional department comprises volunteer and career operations, sees it differently: “The age of PPE and SCBA is also alarming. One-third of the PPE and SCBA is more than two NFPA standards revision cycles old and the technology is out of date; the gear is likely well worn.”

Tom DeSorcy, the chief in tiny Hope, B.C. (population 8,000) is pragmatic. “I think this stat won’t help a department with a low call volume as it’s very hard to justify replacing old equipment that doesn’t appear to get used, at least in the eyes of the ratepayers.”

And Whitehouse, a manufacturer and member of a joint manufacturers-association governmental committee pushing for federal funding for fire equipment, takes a big-picture approach.

“If a safety inspector enters into an industrial establishment and finds someone operating with out-of-date safety equipment there are serious consequences. Why should the same governments that enforce the safety standards for industry be allowed to turn a blind eye when 35 per cent of SCBAs and almost one-third of bunker gear are beyond the age that is generally considered safe for use?”

Len Garis, the chief in Surrey, B.C., worries 10-year-old bunker gear and SCBA do not provide the best personal protection, regardless of the amount of use, given the technological advancements in the last decade.

■ Other equipment

Almost two-thirds of respondents said their fire department has one or more thermal imaging camera; one-third of departments surveyed have no TICs.

“With the price of technology today, it is almost a crime that we can’t equip every truck with this tool that can be so effective at saving the lives of the public and fire service personnel,” says Whitehouse.

Others, like Garis, aren’t so keen on thermal imaging technology.

“I am not personally sold on this equipment,” he Garis. ”It invites firefighters into areas that may not be suitable.”

■ Public education / fire prevention

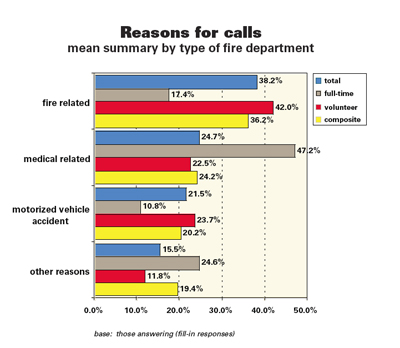

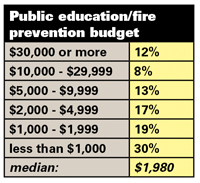

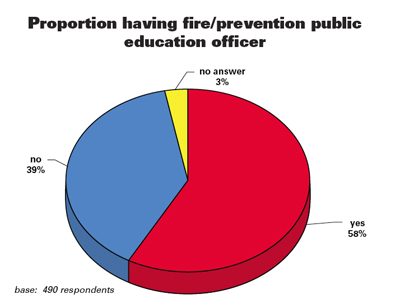

Smoke alarms. Carbon monoxide detectors. Escape plans. We know public education works. But the next step – educating builders and governments about the benefits of residential sprinklers – is a big one. Although 58 per cent of respondents indicated their fire departments have a fire prevention / public education officer, typical respondents indicated their 2008 public education/fire prevention budget was just under $2,000; 30 per cent reported budgets of less than $1,000. Certainly, those numbers apply to volunteer departments and not large, urban centres with full-time public education officers and the budgets to match.

“These numbers are appalling,” Vilneff says. “Fifty per cent of departments have a PE/FP budget of under $2,000! This is, in my humble opinion, definitely the worst statistic in the report.”

■ Training

Respondents were asked about their biggest training challenge. A full list of responses is on our website at www.firefightingincanada.com but here’s a sampling:

- Access to proper training facilities and materials;

- Cost of training courses and cost to travel to courses/facilities;

- Attendance at training sessions;

- Funding;

- No training officer;

- No live fire training facilities;

- Keeping trained volunteers.

Hope, B.C.’s Tom DeSorcy sums it up: “On the subject of training, I can’t help but stress the difficulty in training firefighters to a career standard on a volunteer schedule. It’s next to impossible. Yes, training dollars are important but you can’t buy time.”

Garis offers some solutions.

“We hear this loud and clear in B.C. from both career and volunteer. I think this is mostly driven by standards that make it harder to meet, especially by volunteers and probably the circular nature of volunteer turnover. Most [volunteers] do not get the experience by the sheer lack of calls. I call this the cycle of concern. It is endless and will get worse as standards drive us even further into professional qualifications.

“Clearly, as the fire service is largely volunteer the cycle of concern needs careful examination; perhaps there needs to be a distinction around qualifications matched with size of service, call experience, risk in the community served to grade of service provided. Oh, and, of course, liability is a strong driver; perhaps an exemption might relieve some of this pressure.”

Vilneff says the short-term fix is to pump more money into fire departments as was done several years ago in Ontario through government grants. Long term, Vilneff says, municipalities and the public have to think differently about their fire departments.

“Instead of calling our fire departments and firefighters volunteers, let’s call them by their correct name. It is a municipal fire department and the firefighters are paid on-call firefighters. Unless they are true volunteers, then the name should be ditched.

“As long as we continue to refer to ourselves as volunteer, there will not be the profile (and respect and budget) given to the departments by politicians and the public. I don’t think that we can depend on the departments to initiate this change; it should come from the fire marshal’s office in each province as an initiative or directive.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Volunteer Vision: Getting our training priorities straight

- Back to Basics: Re-introducing the 2.5-inch hose