Features

Hot topics

Labour relations

The 24-hour debate

In January, the Kitchener Fire Department in Ontario adopted a 24-hour shift for its 188 full-time firefighters.

April 12, 2010

By James Careless and Laura King

In January, the Kitchener Fire Department in Ontario adopted a 24-hour shift for its 188 full-time firefighters. Kitchener is the ninth Ontario department to try the 24-hour shift as support for the longer workday and its touted lifestyle benefits gains momentum among Canadian firefighters and their unions.

“We’re still in the honeymoon phase,” says Kitchener Fire Chief Tim Beckett. “It’s too early to tell if it’s working.”

While most Canadian fire departments still use 10-14 shifts or variations, some cities outside Ontario, including Calgary, are starting to hear union rumblings of support for the longer shifts. Fire chiefs associations expect the trend toward the longer shifts to spread as Ontario departments work out kinks in the system and more firefighters in other regions grasp the notion and bring it to their unions.

While the 24-hour shifts appear to work for some departments – Windsor and Woodstock, Ont., have had 24-hour shifts for years – some fire chiefs are wrestling with the lengthy shift and its human resources and management challenges.

At the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs labour relations seminar in January, several chief officers and HR managers participated in a forum on the 24-hour shift. Their thoughts? Generally, young firefighters tend to like the 24-hour shifts because working just seven days a month allows for more time to do other things. Veteran firefighters almost universally despise the longer shifts because their bodies can’t cope with the lack of sleep. And platoon chiefs, in particular, who have to stay awake for the entire 24-hour shift, find the hours onerous.

Some departments that have adopted or attempted 24-hour shifts can rhyme off a litany of administrative headaches: sick days need to be redefined – is one 24-hour shift one sick day or two or three?; training schedules need to be amended – firefighters can’t train for an entire 24-hour shift, but getting the required amount of training in on seven shifts a month is next to impossible; and grievance procedures have to be modified – generally grievances must be filed within seven days of an incident but what if a firefighter isn’t on duty for several days following the incident? One major quibble among fire service managers is what they call the “disconnect” between firefighters who work 24-hour shifts and the department, again because the firefighters are in the fire hall just seven days a month.

Other chiefs say the 24-hour shift has its share of challenges but so do all other shift configurations.

There’s an enormous amount of research on the effect of 24-hour shifts on the likes of medical interns and assembly line workers but no conclusive studies about the impact of the 24-hour shift on firefighters and how being awake for 24 hours affects their abilities to do their jobs. Managers worry about firefighter safety – if firefighters are called out to a major incident 21 hours into a shift are their cognitive abilities impaired and can they function at 100 per cent in potentially life-threatening situations? What about on-the-job stamina and the risks of driving home after being awake for 24 hours? Proponents counter that firefighters on 14-hour night shifts come to work already tired after being awake all day or working at a second job and are just as tired after work as those who have worked a 24-hour shift.

The background

The 24-hour shift has been the norm in parts of the U.S. for years; indeed, according to a 2006 discussion paper by the Ontario Association of Fire Chief on 24-hour shifts, Minneapolis has used the 24-hour shift for more than 50 years to effectively manage its 56-hour work week operating under a three platoon system.

In Canada, Windsor adopted the 24-hour shift in 1965 as a system for managing its 48-hour work week (rather than the standard 42-hour week) while Woodstock’s suppression division adopted it in 1996 to reduce absenteeism on weekends.

The London Fire Service in Ontario adopted a 24-hour shift in 1997 when the city faced fiscal pressures and would have had to lay off eight firefighters. The London Professional Fire Fighters Association proposed the implementation of a 24-hour shift schedule to avoid layoffs. Since then, Barrie, Kingston, Mississauga, Newmarket, Oakville and Toronto have adopted 24-hour shifts, Kitchener is doing a three-year trial and Peterborough recently adopted the 24-hour rotation to save money on salaries and sick time.

“The problem with the 10-14 hour rotation is that fatigue built up when you were on the night shifts,’ says Steve Jones, president of the Kitchener Professional Fire Fighters Association. “There was no way you could catch up on sleep in the 10-hour periods between shifts. You would be exhausted and your sleep patterns got all mixed up by the time you came in for that last night.”

In contrast, says Wisconsin-based sleep researcher Dr. Linda Glazner, the 24-hour rotation doesn’t fundamentally disrupt human circadian rhythms, the 24-hour biological cycle that governs living things.

Glazner has compared the impact of 10-14 and 24-hour shifts on firefighters in Toronto, California and New Jersey. Her research has convinced many fire departments to move to the 24-hour rotation.

“A healthy person’s circadian rhythms, which can be measured electronically, look like a ‘sine wave’,” says Glazner. “The circadian rhythms of someone who works the 24-hour rotation conforms to this shape. The circadian rhythms of a 10-14 hour worker do not.”

Glazner agrees that 24-hour workers have to sleep heavily the day after a shift to catch up on rest. But she says the scientific evidence is clear: “Twenty-four hour workers do not suffer the sleep disruptions – and potentially the health problems associated with them – that 10-14 hour workers do.”

Some chiefs in departments that have implemented the 24-hour shift say firefighters seem to like the new shift better than the old 10-14.

“I find that when I ask our employees, they feel better and have improved morale,” says Chief Harold Tulk of the Kingston Fire Department. “On balance, I’d say that 80 to 85 per cent are happy with the change.”

But critics of the 24-hour shift say that although Glazner’s research on sleep is credible, it doesn’t specifically address firefighters and the inherent risks of their jobs.

Chief Mike Figliola of the Greater Toronto Airports Authority opposes the 24-hour rotation even though his department had adopted it.

“The biggest problem with the 24-hour shift is the impact of sleep deprivation,” Figliola says. “Sleep deprivation after 24 hours awake is the equivalent to a blood alcohol level of 0.10. That’s 25 per cent above the legal limit.”

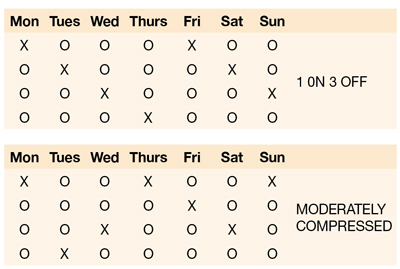

After considerable discussion with the union, Figliola’s department adopted a modified 24-hour shift rotation that provides a minimum of 48 hours off between 24-hour shifts and every second weekend off. It also avoids the traditional Friday on, Saturday off, Sunday on weekend pattern that firefighters and their families find onerous. Figliola says two patterns meet this criteria:

|

| Younger firefighters are said to prefer the 24-hour shift but older workers and managers are less keen on the longer shift rotation.

|

Asked about Figliola’s point about lack of sleep equating to a blood alcohol level of 0.10, Glazner says Figliola is correct “except that this doesn’t happen all the time. Typically, officers on 24-hour shifts get the chance to get some sleep.”

Chief Richard Boyes of the Oakville Fire Department notes that platoon chiefs don’t get such breaks. “They have to be awake the entire 24 hours to monitor what’s going on, and that’s pretty hard on them,” he says.

Figliola is not moved by Glazner’s argument. “The rate of technical errors increases after 16 hours without sleep,” he says. And in those instances where firefighters do not get any sleep – as can happen in busy urban areas – the danger of accidents being caused by sleep deprivation is very real.

“There have been catastrophic events attributed to sleep deprivation,” Figliola says. “They include Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, the Exxon Valdez and the Challenger Explosion.”

The 24-hour rotation costs no more than the 10-14 schedule because the hours balance out over the month. As a result, “there has been no adverse impact on Toronto Fire Services operations,” says Toronto Fire Services Division Chief David Sheen.

“In fact, thanks to the positive benefits that we’ve been able to negotiate with our union, the 24-hour schedule is working for us.”

Toronto Professional Fire Fighters Association President Scott Marks agrees. “We’re up to a 95 per cent approval rating among our members for the 24-hour rotation,” he says.

Training challenges

Training is another issue that worries chiefs, because training officers tend to work a 9-to-5 schedule. “It is hard to get people who are off-shift back in for training classes,” admits Kingston’s Chief Tulk. “Of course, it was hard to get them in during the old 10-14 hour schedule too.”

In the same vein, it is difficult for senior officers to mentor up-and-coming talent simply because they don’t have much contact with one another under the 24-hour rotation.

Another concern is how emotionally connected 24-hour firefighters are to their departments, given that they are on duty just seven days a month.

“We run the risk of fire fighting becoming a well-paid part-time job,” says Chief Figliola. “They are supposed to be relaxing when they are not with us. But we all know how busy firefighters are in their off hours.”

Finally, not everyone is able to adjust to working 24 hours straight. “We find the younger people can handle it, but the experienced people in their 50s find it’s too much,” says Chief Boyes. “In Oakville, we’ve had eight retirements since we made the change [in 2008]. Not all of them were related to going to the 24-hour rotation, but some definitely were.”

In the executive summary of its 2006 report on 24-hour shifts, the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs identified concerns with the 24-hour shift schedule and urged departments to consider a lengthy checklist of items from call volume to sick days before implementing the longer rotation.

“Individuals’ cognitive and physical performance tends to decline after 24 hours without sleep,” the report said. “Occupational health and safety studies indicate longer shifts and shorter rest periods increase the probability that accidents will occur. Moving to a 24-hour shift may increase exposure to legal liability.

“Fire departments considering a change to the 24-hour shift schedule should proceed with caution.”

Print this page