Features

Prevention

Re-framing risk: Using the public-ed matrix for a fresh first-line approach

Smoke alarms. CO alarms. Attended cooking. Clear dryer vents. How many of these topics has your fire department covered the past few years? The answer is likely all of them, yet there goes your crew again – another fire, started in the kitchen, unattended cooking, no smoke alarm.

May 24, 2017

By Tanya Bettridge

Successful campaigns with blunt messaging Despite fire departments' best efforts to inform the public

Successful campaigns with blunt messaging Despite fire departments' best efforts to inform the publicGeorge Bernard Shaw said, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” Shaw was really on to something. The illusion is easily – and understandably – maintained. After all, if repetition is a factor in learning, the fire service has been teaching the same lessons for several decades. Think about it. The 1977 Fire Prevention Week theme was Where There’s Smoke, There Should Be a Smoke Alarm. Forty years later, we’re still working on that. Most fire-safety communication includes a message about smoke alarms.

The messaging has not kept up with our audiences (that’s been covered in other stories and blogs) but we need to ask ourselves why people don’t seem concerned about being injured or killed by fire.

■ The risk matrix

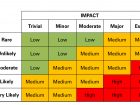

If your fire department has ever done a risk assessment, chances are you’ve used the risk matrix: probability + impact = risk.

People don’t care as much about fire safety as they should because they underestimate the probability and the impact; people are even more oblivious to the risk of a fire than they are to a vehicle collision. You are too, if you’ve ever exceeded the speed limit. Ah, got ya there, didn’t I? How many vehicle collisions occur everyday in the communities along your commute? What are the catastrophic consequences of a vehicle collision? Firefighters know the answers better than most, yet I bet you, just like other drivers, exceed 100 kilometres per hour on major highways despite all the fatal collisions you’ve witnessed. And now you know why people pull batteries out of annoying smoke alarms, or leave the kitchen while cooking – because it’s acceptable to ignore the rules. Despite best efforts to educate people about working smoke alarms and attended cooking, and despite the efforts to create laws, codes and even speed limits, the risk is underrated or ignored.

The solution is simple, but its implementation is more complex and requires acceptance by all stakeholders: we’re going to have to set aside the family-friendly, approved-for-all audiences approach to public education in favour of a harder-hitting, more harsh, in-your-face campaign.

I remember, as a teenager, impaired driving emerged as a dangerous trend for young people. I recall stories of teens and twenty-somethings being taken to morgues, funerals and prisons to give them a taste of what can happen; they seemingly became different people overnight, vowing to never, ever drink and drive again.

A hard-hitting, high school program in the United States called Every 15 Minutes drives home the statistic that every 15 minutes someone is killed by an impaired or distracted driver. In high schools, a student is pulled from the classroom every 15 minutes, returning as the living dead, with white face make up, a coroner’s tag, and a black Every 15 Minutes t-shirt. By the end of the program, students have written their own obituaries, received a letter from their parents, heard an audio-visualization of their own deaths, and experienced mock scenarios that involved everyone from first responders to police-station booking officers to the coroner.

The program is effective because it elevates the impact rating of the risk matrix. Every 15 Minutes elevates both probability and impact, reinforcing how often people die from impaired driving and the consequences of those incidents.

Imagine if instead of receiving a speeding ticket you had to go talk to the parents of a child who died in a speed-related collision; you have to tell those parents why you choose to speed. You have to listen to the parents talk about the loss of their child. Which do you think is more effective, being made to have that conservation or being told to pay your ticket and obey the speed limit because it’s the law?

As public educators, it’s time to brainstorm how we can create similar programs and set aside ultra-appropriateness in favour of something that works and saves lives.

■ The public-ed matrix

Essentially, the fire service has limited the matrix tool to simply identifying risks in our communities, instead of using it to educate people about the magnitude of the risk.

What if Mr. and Mrs. Smith consider the probability of a fire occurring as the only factor in whether or not they need smoke alarms? Since fires don’t happen very often in their community, they believe the probability is unlikely. Therefore, to the Smiths, there is no real risk.

What if the Smiths had to listen to a 911 call that involved people trapped in a house fire? What if they had to listen to young people dying? Afterward, what if they were given statistics on how many people die in house fires every year? Then, what if they were told how many may people have survived because they had working smoke alarms? What if the Smiths were given a choice: paying a hefty fine or tagging along for a visit to a hospital burn unit?

Organizations like Every 15 Minutes have figured out this matrix and use it to their advantage: probability + impact = rate of behaviour change.

- People have to understand that fires can – and will – happen

- People need to understand and assess a high value on the consequences of fire

- The higher those two factors are, the more likely people are to act

■ outlaws

“It’s the law” messaging worked decades ago, when authority was unquestioned; if the fire department told people to do something, they did it. Today, people need to be motivated to want to change.

Few Canadian departments have the resources to implement programs such as Every 15 Minutes. So maybe it’s time to think big picture – literally. We could partner with people in the film industry to record one person’s journey; perhaps Hearts On Fire could be the next big Netflix documentary and affect positive change. One willing “outlaw” would tour the site of a fire, visit a burn unit, talk to a family that lost someone in a fire and end with an interview about the experience. Don’t think it’ll work? Ask SeaWorld how it felt about the documentary Blackfish.

■ Before we’re famous

A Netflix documentary is a long way off; so what can fire departments do in the meantime? Many departments have implemented the very effective After the Fire program, through which personnel conduct door-to-door visits in the area after a house fire. Members talk to neighbours, check smoke alarms, and attract kids with the parked apparatus.

Fire departments often credit timing for the effectiveness of After the Fire. But what really happens is a shift in the public-education matrix. Essentially, the visits by fire-department personnel, who explain that the family lost everything, increase the probability factor in the minds of area residents. If your fire department has this kind of program, which uses motivational factors that affect behavioural change, bravo!

We can no longer demand change, but we can inspire it.

Tanya Bettridge is an administrative assistant and public educator for the Perth East and West Perth fire departments in Ontario. Email Tanya at tbettridge@pertheast.ca and follow her on Twitter @PEFDPubEd

Print this page

Advertisement

- Trainer’s Corner June 2017: A firefighters’ ovation for ventilation

- Firelines: Embracing education in the fire service