Features

Trainer’s Corner: Communication is the foundation

February 16, 2021

By Ed Brouwer

Check out the first Trainer’s Corner, which has now been helping the volunteer training officer for 20 years.

Photo by ED BROUWER

Check out the first Trainer’s Corner, which has now been helping the volunteer training officer for 20 years.

Photo by ED BROUWER This year marks the 20th anniversary of Trainer’s Corner and I am filled with gratitude for this incredible opportunity afforded to me by Fire Fighting in Canada. Jim Hailey the editor at that time, was very supportive of the idea for a feature column addressing the needs of the volunteer training officer.

The opening paragraph for my first column read: “This column will hopefully be viewed as a great resource for the volunteer fire service training officer. The intention here is to provide some tried and tested training drills that are “do-able” with our limited budgets. This first one is simple to set up and yet challenging enough to keep your members’ interest.”

I thought you might want to look back with me at the first issue.

Communications drill

Time required: About 10 minutes per team.

Objective: Sharpen radio communication skills and encourage the “thinking” process.

Items needed: Duct tape, stopwatch, two portable radios, four stacking chairs.

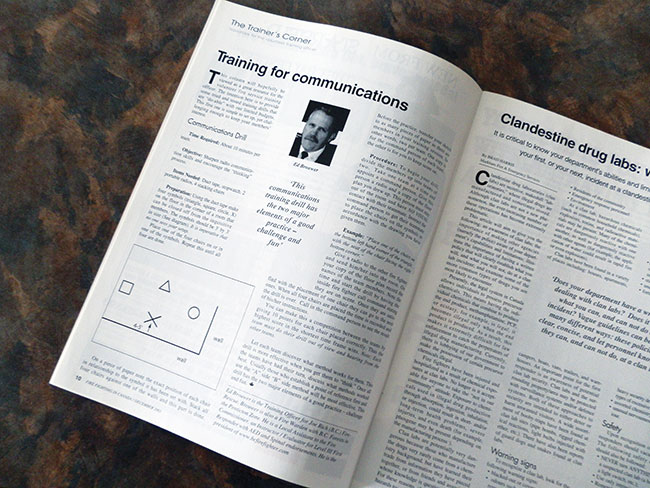

Preparation: Using the duct tape make four symbols (triangle, square, circle, X) on the floor in the corner of the room that can be closed off from the inquisitive members. The symbols should be three feet by three feet in size.

It is imperative that no one sees your setup.

Place one of the four chairs on or in one of the symbols. Repeat this until all four are done.

On a piece of paper note the exact position of each chair in relationship to the symbol it has been set with. Stack all four chairs against one of the walls and this part is done.

Before the practice, transfer your sketch to as many pieces of paper as there are members in your training session. In other words, two per team. One copy is for the command person of each team, the other is for you to keep score on.

Procedure: To begin your drill, divide the members up into teams of two. Take one team at a time and appoint a command person. Give this person a radio and a copy of the floor plan you drew up. This person must stay out of the room and have NO VISUAL contact with their teammate. Instruct the command person to get their teammate to place the chairs on the symbols in accordance with the drawing you have given them.

Give a radio to the other fire fighter and send him/her into the room. On your copy of the floor plan record the names of the team members. Note the time and start the drill by having the inside fire fighter call command stating they are on scene. Once they are satisfied with the placement of one chair they can go to the next ones. When all four chairs are placed the time is recorded and the drill is over. Call in the command person to see the result of his/her instructions.

You can make this a competition between the teams by giving 10 points for each chair placed correctly. The highest score in the shortest time frame wins. Note: Each team must do their drill out of view and hearing from the other teams.

Let each team discover what method works for them. This drill is more effective when you get them to “think”. Once all the teams have had their turn, discuss what methods worked best. Usually those who established a point of reference first and us the “A” side “B” side method will be most effective. This drill has the two major elements of a good practice – challenge and fun.

Over the years we have built on that first hands-on lesson to address that one universal fire ground problem — communications. Looking back on the previous column, you will see that “communications” is a common thread that runs through each lesson plan.

Whether the topic is arrival reports, size-up, mayday protocols, office training or even PTSD, communication skills are foundational building blocks. Good communication skills are not just necessary on the fireground, they are vital within the fire department. In fact, good communications are vital for successful relationships in all of life.

We have all witnessed the fall out when somebody fails to communicate clearly or in a timely manner and a misunderstanding occurs. Many a fire hall has been negatively affected by problems with communications.

There are two factors that contribute to communication problems on the fireground: hardware and human. Weak radio signals, SCBA muffled radio transmissions, dead or dying batteries, and my favorite, trying to operate a radio with gloves on while looking through your BA mask in the dark. The hardware problems are often easier to fix than the human caused issues. Not speaking clearly, not holding the radio properly, excessive radio chatter and speaking before keying the mic are but a few.

Inevitably when our entry teams were in the middle of interior fire operations, like dragging a fully charged line up a flight of stairs the IC would call “just” to see how they were doing. Not just once, but several times the team would have to stop their ascent, fumble with gloved hands for the radio and then struggle to make themselves understood.

To deal with this situation we agreed to purchase clip on mics. We also gave our members permission to postpone responding to the IC’s call by saying, “stand-by one,” until they were in a safe position to do so. Simple changes, but a big stress reliever. And yes, we dealt with our IC.

Many misunderstandings on the fireground can be addressed with the introduction of one unassuming word: From. Firefighters must be taught this word during their basic radio communications training. Simply put when one radio connects with another radio, firefighters should always use the word “from”. So, if you the IC want to communicate with Engine 1, you would say, “Engine 1 from IC”. It is important you get Engine 1’s attention. If you had said, “IC to Engine 1”, Engine 1 may have missed who was calling. Consider listening to radio traffic at a typical call out. It is only when you hear your call sign that your brain engages your ears to really pay attention. So again, using “from” not “to” it would be “Engine 1 from IC”, the response from Engine 1 should then be “Go ahead IC.” This would prevent responses such as, “Say again for Engine 1.”

Speaking of responding, it is important to acknowledge that information was received. However, saying “copy” or “got it” is not sufficient. Firefighters should be taught to repeat part of the message back to the speaker. If you do this consistently during practice scenarios, fireground incidents and mop up, it will become second nature. Teach, for example: “Engine One from Attack One” — “Go Ahead Attack One” — “We need 100 psi on line one” — “Roger that, 100 psi line one.” By repeating the request any miscommunication is nipped in the bud.

Miscommunication on the fireground can have fatal consequences. You need only read one fatality report to understand that poor communications negatively affect situational awareness, which is a major contributing factor for firefighter injuries and fatalities.

For many years I have signed off my columns with, “Train like lives depend on it…. because they do”. This was always directed more to the lives of your fellow firefighters than the public. Thank you for the great job you are doing… respect. Please stay safe and be sure to look after yourself.

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., retired deputy chief training officer for Greenwood Fire and Rescue, a fire warden, wildland urban interface fire-suppression instructor and ordained disaster-response chaplain. Contact Ed at aka-opa@hotmail.com.

Print this page

Advertisement

- Fire Fighting in Canada This Week – February 12, 2021

- Fire College closure should have minimal impact on northern fire departments