Features

Fire & EMS

Unintended consequences: The opioid crisis and COVID-19

Opioid deaths on the rise in Canada amid the COVID-19 pandemic

July 14, 2020

By

Brieanna Charlebois

The Vancouver fire department partnered with Vancouver Coastal Health to create an interagency response team.

Credit: Vancouver Fire Department

The Vancouver fire department partnered with Vancouver Coastal Health to create an interagency response team.

Credit: Vancouver Fire Department

While Canada’s number of new daily COVID-19 cases has been dropping, the death toll from another ongoing public health crisis is rising. In recent months, provinces and territories across Canada began reporting a growing number of opioid-related deaths.

In a statement released on May 31, Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, addressed the increasing overdose trends across the country.

“While everyone in Canada is working hard in the fight against COVID-19, there is an increasing concern about a range of unintended negative consequences of the pandemic response,” Tam wrote. “Among these is the impact on the ongoing public health crisis of opioid-related overdose deaths and problematic substance use in Canada more broadly.”

Increased opioid overdose numbers have been cited in jurisdictions in Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Saskatchewan and the Yukon.

The Ontario’s Coroner’s Office cited a 25 per cent increase in the number of overdose-related deaths from March to May over the same period last year.

In Alberta, the number of opioid-related calls to EMS increased from 257 in March to 550 in May and the Calgary Drop-In Centre’s staff said they reversed over 40 overdoses in both March and April this year compared to 11 in February.

The city of Winnipeg also reported that emergency calls related to crystal meth and opioid poisonings or overdoses had increased 66 per cent in April and May, compared to the same period last year.

In British Columbia, the Coroners Service found that unintentional illicit drug toxicity deaths have increased in recent months, with over 100 reported deaths occurring in the province in both March and April. The province, which declared the opioid epidemic a public health crisis in 2016, also reported 170 fatal overdoses in May alone—more deaths in a single month than COVID-19 had claimed in the province at that date.

Across the nation, the overdose crisis has been largely driven by increasing contamination of the illicit drug supply with powerful synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

“Even before COVID-19, the overdose crisis had been raging for years, but one thing we’re seeing now is that the ability to connect and try to support people who are using drugs has really become a lot more difficult,” said Nick Boyce, director of the Ontario Harm Reduction Network.

He explained that though overdose prevention sites remained open, physical distancing guidelines meant fewer people had access to services. This, combined with increased isolation (meaning more people using alone) and a general fear of catching the virus are also likely deterrents during the pandemic.

While no official reason for more potent and toxic drug supply has been confirmed, some experts have suggested that, because the global supply chains were broken down after COVID-19 and measures were put in place and borders closed, more potentially deadly drugs began circulating to make up for lack of supply.

But, Andy Watson, spokesperson for the BC Coroners Service, urged caution in citing reasons for the preliminary data until evidence-based research is found.

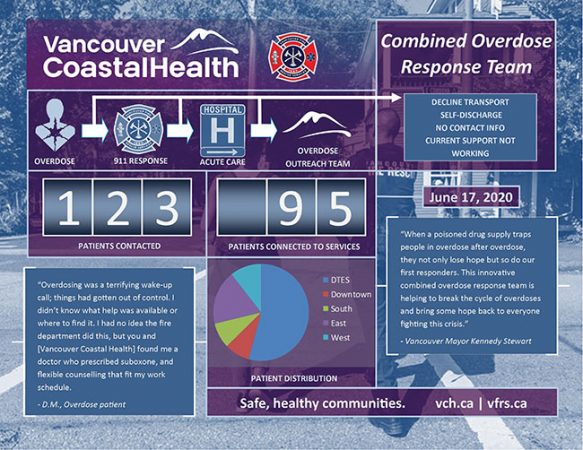

Vancouver Combined Overdose Response Team operational system and progress as of June 17.

Credit: Vancouver Coastal Health/ Vancouver Fire Department

“Since 2016, we’ve been dealing with a highly toxic drug supply with fentanyl detected in about nine out of 10 deaths and we have seen, certainly in the last few months, that the level of toxicity and fentanyl concentration in the post mortem testing is even higher,” said Watson. “We continue to see it detected in about nine out of every 10 deaths but now it’s a higher toxicity to what we would consider an extreme level.”

Of course, an increase in overdoses takes a toll on responders who are often the first on scene.

In April, the Vancouver department made headlines after calling on Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry to reconsider an order restricting firefighters to attending only the most life-threatening calls, saying the unintended consequences of the decision put citizens at serious risk.

Jonathan Gormick, the Vancouver Fire Rescue media relations officer, said COVID-19 measures had taken a toll on the department (even before medical calls were limited) about navigating how best to respond to patients exhibiting COVID-like symptoms and having the proper PPE, but limiting medical calls was an added concern.

“Our response matters, especially when someone’s in respiratory arrest. Seconds count and the faster that we get professionals on scene who are able to provide ventilations or interventions like naloxone, the better chance we have of a positive outcome.”

The decision was reversed shortly after so the department could continue responding to overdoses.

“I think it’s really important for us to recognize the crucial role that all first responders, including firefighters, have in reversing overdose events that would otherwise be fatal,” said Watson. “So, in order to help departments, access to safer supply is really crucial because the fewer calls they have to attend, the more that can be done in other ways.”

Many fire departments across the country, including the Vancouver department, began taking naloxone to calls in response to the increased numbers of overdoses in recent years. Other measures have been put in place in various provinces in an attempt to now address the dual crises.

For example, on March 17, the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions in British Columbia also implemented ‘Risk Mitigation in the Context of Dual Public Health Emergencies’ guidance in an effort to protect people from the risk of withdrawal, overdose and COVID-19.

“Physical distancing is not easy when you are living in poverty, visiting a clinic every day to get your medicine and relying on an unpredictable, illegal drug supply,” said Judy Darcy, Minister of Mental Health and Addictions. “This guidance will make it easier for at-risk people to meet the requirements of distancing while avoiding other serious risks to their health and to the health of the community.”

The guidance is the first of its kind in Canada where people can access a prescription through a doctor, nurse practitioner, or through outreach teams and clinics to support prescribers and increase access to those who need safer alternatives to toxic street drugs.

In an emailed statement to Fire Fighting in Canada, Heidi Zilkie, communications manager for the Ministry wrote, “This guidance is just one piece of a much bigger puzzle; we are working to create a more comprehensive system of substance use care from harm reduction to treatment and recovery.”

While the Ministry said this is interim guidance, they will continue to evaluate its effectiveness and will update as needed.

In response to growing concerns since being deemed a public health crisis in 2016, Gormick said that in August 2019 the Vancouver department also launched a Combined Overdose Response Team in partnership with Vancouver Coastal Health social workers to follow up with and connect overdose patients to support services that decrease the probability of subsequent overdoses.

“As the [overdose] numbers continued to climb, we kept adding response resources,” he said. “I think this has proven to be an extremely effective strategy to not just attend and reverse overdoses but to address the factors that result in an overdose.”

He said this interagency partnership was successful as shown in decreased numbers of overdose rates in late 2019, prior to the pandemic.

Another measure came in May. To address concerns surrounding those doing drugs alone and allowing more access to the supports needed, British Columbia’s Provincial Health Services Authority in partnership with regional health authorities and Lifeguard Digital Health, launched a new resource called Lifeguard App.

Activated by the user before they take their dose, after 50 seconds the app will sound an alarm and if the user doesn’t hit a button to stop the alarm (indicating they are fine), the alarm grows louder. After 75 seconds a text-to-voice call will go straight to 9-1-1, alerting emergency medical dispatchers of a potential overdose. The app is now being added to the list of essential health and social sector interventions as part of the comprehensive response to the sustained and widespread overdose activity in the province during COVID-19.

While medical professionals urge Canadians to continue practicing public health measures to limit the spread of COVID-19, changes to drug supply in the wake of the pandemic highlight the importance of maintaining active treatment and harm reduction services for drug users, with many experts calling for legislative changes and more support for frontline workers.

“We know that federal changes won’t happen overnight but we’ll continue to advocate for decriminalization, said Watson. “Bottom line, the goal of making sure people can use safely, without fear of coming across a bad match through the illicit market.”

Print this page