Features

Hot topics

Wildfire Week

Co-ordinated effort: Crews in British Columbia manage wildfires with mutual-aid system

The fire fight in British Columbia in the summer of 2017 was a deliberate, military-like series of operations born of the 2003 Okanagan Mountain Park blaze.

August 24, 2017

By

Laura King

Firefighters from municipal departments across British Columbia worked with BCWildfire Service to extinguish the hundreds of human-cased and lightening-started fires this summer. Editor Laura King finds that the fire fight in British Columbia is a deliberate military-like operation born of the 2003 Okanagan Mountain Park blaze.

Firefighters from municipal departments across British Columbia worked with BCWildfire Service to extinguish the hundreds of human-cased and lightening-started fires this summer. Editor Laura King finds that the fire fight in British Columbia is a deliberate military-like operation born of the 2003 Okanagan Mountain Park blaze.Things went wrong back then: hundreds of homes were leveled; more than 250,000 hectares burned.

The subsequent inquiry into prevention, planning and response was the caveat for a document that helped to make the 2017 fire fight as seamless and effective as such a massive undertaking can be.

Robert Krause worked for 36 years with the BC Wildfire Service, the last 11 as a type-1 incident commander. Krause is now the chief in Burns Lake, but has an agreement with the village that allows him to coach new incident commanders at wildfire scenes. He was twice deployed this summer.

“The biggest thing is everyone has a better understanding of how the process is supposed to work, and what their roles and responses are,” Krause said.

“When we’re speaking to the public and meeting with local government, for example, everyone understands that dealing with evacuations is [municipal] responsibility and BC Wildfire is dealing with the fire.”

The 27-page inquiry document, titled Interagency Operation Procedures and Reimbursement Rates, outlines how the province can request resources, explains the deployment model, pinpoints costs for trucks and firefighters, and details the steps to follow for structural protection.

It is, says Hope Fire Chief Tom DeSorcy, is a bible for those managing resources.

Every fire department in British Columbia has a standing mutual-aid agreement with BC Wildfire: if the municipality calls BC Wildfire, the municipality pays; if BC Wildfire calls the municipality, the province pays.

The document lists rates for apparatuses and firefighters – paid on-call, volunteer, and career – and takes into account collective agreements.

“Before the season begins,” DeSorcy said, “the request goes out from the Office of the Fire Commissioner. We will come forward with a list of available units should they need to be used.”

It’s tough, DeSorcy acknowledges, for a volunteer department to offer resources in early spring, not knowing how many volunteer firefighters will be available at a given time.

“We could offer a tender or a compressed-air foam bush truck, or an engine, and then they could call us and ask us [for it].”

On July 11, at the height of the 2017 wildfire season, the province requested that Hope’s tender respond to Williams Lake.

“So I put the call out,” DeSorcy said. “I had pre-warned the volunteers, so some had prearranged things with their employers, and I was fortunate enough to get a couple of people to go at a moment’s notice.

“It’s interesting to pack up the truck and make sure it’s ready to go; [our firefighters are] not used to going for a 400-kilometre run . . .”

And in a 1999 tanker, no less.

“I’d like to send the newer vehicle for creature comforts,” DeSorcy explained, coyly. “But this particular vehicle was sent because these particular operators didn’t have air tickets.

“It was a 1999 Ford water tender, and it was the work horse going down mountain roads in Williams Lake.”

Back in 2003, and during the Salmon Arm fire in 1998, some departments self-deployed, causing confusion.

“I remember the image of all the trucks on the Coquihalla Highway,” DeSorcy said, “lined up at the toll booth, and no one would let them go through without paying – there was no provincial state of emergency and no one knew to let the trucks through. These departments just took it upon themselves to respond.”

Now, the Office of the Fire Commissioner has the authority once a state of emergency is called to create a provincial fire department and call for trucks from municipalities; those resources are then used for structural protection while BC Wildfire manages the forest fires.

“There’s a partnership with Office of the Fire Commissioner,” said Krause, “that they handle all of the structural firefighting assets. They’re the ones who are able to bring the additional resources into the communities.”

In the summer of 2017, municipal departments voluntarily offered up trucks – spare tenders or pumpers; there was no need for the province to demand resources.

Jason deJong is the fire rescue services co-ordinator for the Cowichan Valley Regional District on Vancouver Island. He spent 11 days in Williams Lake as an incident commander and says the system implemented post-2003 works.

“The provincial fire department established by the Office of the Fire Commissioner was set up well in advance of main fire front moving through Williams Lake,” deJong said in an interview.

“We had between 30 and 40 fire trucks, engines and tenders. The command structure was set up; the task-force structure was set up. All the prep work was developed for each day.

“Obviously, there was a list of priorities and jobs that needed to be done and as we had time through the subsequent days we would get to those jobs and extend out to more houses and ranches and buildings, even working our way back to town where subdivisions are, FireSmarting homes, working zone by zone, pulling away combustible debris and stuff like that.

“There was a lot of work and preparation ahead of time . . . It has been working out well.”

Under the agreement, communities are reimbursed by the province for offering up their trucks, volunteer firefighters are paid to be away from their jobs, and relationships developed through membership in the Fire Chiefs Association of BC (FCABC) has improved communication.

“I know a lot more people in this business than I did in 2003,” said DeSorcy, who helps the FCABC with communication. “We are keeping members informed, sending out information that in 2003 I didn’t have – for example, what it means when state of emergency is called, and who’s doing what. I think it’s making a huge difference.”

Indeed, several current or retired chiefs have stepped up to help the Office of the Fire Commissioner, and those chiefs are liaising with the FCABC, which is sharing information through social media.

“We’re local assistants to the fire commissioner,” DeSorcy said, “and they’re using us in that role.”

Overall, deJong said, the system functions efficiently and effectively.

“There was a lot of brain power up there [in Williams Lake] and the organization was great,” deJong said.

“There is a lot of stuff I can take back from there – the command structure and the knowledge behind it. It was a real treat to see. Everyone worked well together. Everyone should be proud.”

In mid-August, BC Wildfire confirmed that the province was experiencing its worst season on record – 894,941 hectares of land had burned since April 1. Several of the larger fires started within days of each other in early July, and burned all summer.

“They all started in about a one-week stretch of time,” said Krause, “a combination of human-caused and a lightening storm that came through.

“We have six type-1 incident-management teams in the province, and all six of those were launched in a five-day period in July, so that immediately puts a huge strain on our ability to manage incidents. Then you’re starting to look at going out of province and out of country to allow for your rest cycles. ”

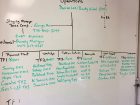

The six teams vary in size from 11 to 13 people including the incident commander, four section chiefs – operations, planning, logistics, and finance – a safety officer, an information officer, and an air-branch director. Teams can have any number of other positions, and up to four trainees for the key IMS roles.

Krause was deployed to the Gustafsen fire near 100 Mile House, to assist the teams.

“We helped deal with the evacuation of 100 Mile House the night the fire jumped Highway 97 just north of the community,” Krause said. “I was in the EOC for the municipality and helped co-ordinate among RCMP, local government, and Transportation and Highways.”

Krause was back home in Burns Lake in mid-August, but only briefly, then deployed again as hot, dry weather fuelled the fires.

“There are numerous units and structural-protection sprinkler crews that are still out in the rural areas,” Krause said, “and still hundreds of structures that have structural protection and are still being triaged.”

The province has an arsenal of structural-protection equipment, lots of it purchased post-2003. But in a year like this, Krause said, “obviously we don’t have enough in the province and we have imported some from Ontario and Alberta.”

The biggest challenges, Krause said, are managing resources and keeping up with the changing fire patterns.

“From an incident-management perspective, we need to prioritize the limited number of resources we have available. You hear that B.C. is getting 400 out-of-province resources but they have to get spread among seven or eight fires and suddenly you’re getting only 40 firefighters on the ground; the Elephant Hill fire is 40,000 hectares or larger – so 40 firefighters are a drop in the bucket.

“The other challenge is changing priorities. With fires this big, you might be having great success in one area but in a another, because of wind direction, the fire is burning homes. The fires are massive and trying to organize and manage the safety of responder sand the public is an enormous task.”

That’s exactly what happened to deJong. He was requested by the Office of the Fire Commissioner to head to Williams Lake to be a task-force leader.

“When I arrived, there was a basic description to show up at the command post for next day. I was partnered with Chief Paul Hurst from View Royal, and we had five or six units attached to us.

“Initially, we were assigned to a certain part of the city in Williams Lake to solidify the sprinkler units and protect a school and certain areas of a subdivision. That night, our role changed a bit. There were other task forces that were assigned to some of the larger saw mills and plywood mills, and we were assigned to assist them setting up . . . Later that evening, the fire progressed across the Fraser River and that’s when the tactical decision was made to evacuate the town.

“We went back to the fire areas to set up structural protection for houses that survived, and set up more structure protection for the mills and the residents that were really close to the fire area. We were working with a couple of crews from Ontario, from the Ministry of Natural Resources, and they had two type-1 trailers come in, and we were setting up sprinkler units and bladder tanks.”

British Columbia has had incident-management teams for some time – in the 80s and 90s, before the province adopted the incident management system, they were called overhead teams – and the post-2003 agreement has been updated several times, most recently in May. Yet DeSorcy says there’s still confusion among taxpayers about how the system works.

“People don’t understand what goes on behind the scenes, and maybe we can do a better job to explain why and how we do this,” he said.

Mainly, DeSorcy said, people become concerned when they learn that one of their town’s fire trucks is elsewhere.

“People think, Oh you’ve sent our fire truck away. [They don’t understand that] we have mutual aid, we have backfill. We’re not just deploying people – it was requested of us because they knew what we had a truck available to send. It’s organized.”

The other common concern is evacuations.

“People want to know what happens if we have to evacuate, what happens if we have a fire close by,” DeSorcy said.

“We do our best to say yes we have a plan – we have an evacuation plan in our area that’s ready to go. There are two types of evacuations: one is tactical, if a fire is impinging on a home right now; the other is an alert system.

“It’s well planned, but the public thinks well, maybe we didn’t have to leave this soon. It’s very hard for a community like Williams Lake to say leave – everybody. When do you make that decision? You don’t wait until the flames are licking at your doorstep.”

Over on Vancouver Island, which by mid-August had escaped any major wildfires, deJong had former wildfire-branch employees study weather statistics; they determined that wildfire season starts earlier that it used to, and there are more high and extreme days, on average.

“We compared ourselves to Penticton,” deJong said, “and most people wouldn’t think so, but south island has a lot of similarities; we’re in high to extreme.”

And that, says Krause, is becoming the norm.

“The end,” Krause said over the phone on Aug. 16, “is going to come when we get a true change in the weather. We’ve had a downturn in weather the last three days so we’re making progress, but overall it’s drought for the summer, and it’s still there, and all it’s going to take is two or three days of hot weather again . . . they’re going to continue to burn until we get our fall rain.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- From the editor: Back to (fire) school

- Brotherhood and best practices: Learning the value of teamwork in Williams Lake