Features

Emergency & disaster management

Hot topics

EMS Focus: Handling the mass casualty incident, creating order out of chaos

Handling the Mass Casualty Incident: Creating order out of chaos

December 13, 2007

By Barry Bouwsema

Potentially, sometime in every emergency responder’s career, he or she may be faced with the emergency call where the needs of situation overwhelm the resources available. Whether it is a bus crash, building collapse or hurricane; if there are more injured patients than there are responders, the scene can be considered a mass casualty incident (MCI). Creating order out of chaos is not an easy task. Proper triage will give the emergency responder the tools needed to prioritize actions when faced with an overwhelming number of conflicting priorities.

By definition, an MCI exists when one of the following situations occurs:

• the number of patients and the nature of their injuries make the normal level of stabilization and care within an acceptable timeframe extremely difficult or unachievable;

• and/or, the resources (personnel/equipment) available for the number of patients are inadequate;

• and/or, the stabilization capabilities of the hospitals that can be reached within an acceptable timeframe are insufficient to handle all the patients.

The proper handling of an MCI requires a systematic approach to the triage, treatment and rapid transport of multiple casualties. The type of response requires a change in the normal operating procedure to achieve the ‘greatest good’ for the greatest number of casualties, without expending an inordinate number of limited resources. The basic principles applied in the handling of an MCI include: Do the greatest good for the greatest number. Make the best use of personnel, equipment and facility resources. Do not relocate the disaster.

During an MCI, operational procedures are designed to organize a response to a specific incident or need, with efficiency as the goal. Normal patient care procedures are relatively inefficient in terms of speed and resource commitment in an MCI situation. If these same procedures are used in a multiple or mass casualty event, they result in unacceptably long times to clear all patients from the emergency scene. Therefore, an MCI requires the use of emergency procedures such as “S.T.A.R.T. – Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment.”

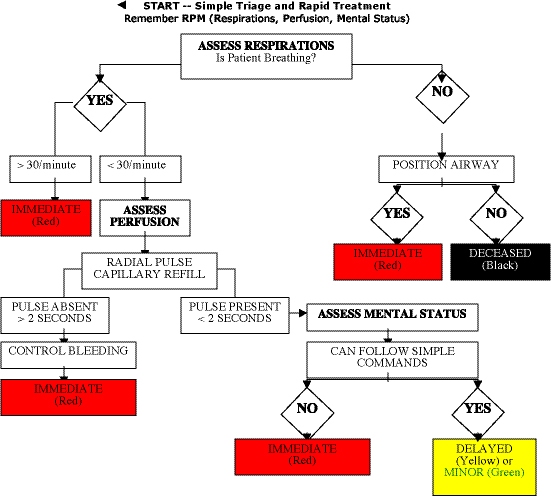

START triage was developed by the Newport Beach Fire and Marine Department in the United States to quickly identify and sort patients during a multiple patient incident. START quickly distinguishes between critically ill victims and the less-severely injured. Following a specific algorithm, an emergency medical services (EMS) responder quickly assesses airway, respiration, pulse and level of consciousness to categorize a patient’s condition. With START, an EMS responder can assess one patient every 30 seconds. The only treatment rendered by the EMS responder is to open a patient’s airway by insertion of a BLS airway, or to apply direct pressure to stop an obvious bleed or by elevating the extremities.

The goal of any comprehensive EMS system is to have all high priority or “Red” categorized MCI patients transported and/or receiving definitive care within one hour of the incident occurring.

Key concepts of triage

Using the START system, patients are triaged into four colour-coded categories indicating priority for treatment/transport. The triage tag or coloured tape should be placed on the left ankle; if this extremity is not available then placement of the tag on the right ankle is acceptable.

Triage is based on three vital signs – respirations, pulse and mental status (RPM). By assessing these three vital signs the patients are sorted into four colour categories: RED, YELLOW, GREEN, and BLACK. Any patient with significantly altered RPM requires an immediate transport and is colour-coded RED. Patients who are unable to follow instructions to evacuate the scene, but whose “RPM” is intact, are categorized YELLOW. This is the most common category. It also includes patients who have a significant mechanism of injury, but whose “RPM” is unaltered. GREEN patients are those at large incidents who were able to leave the impact area on the instruction of EMS personnel. They are the “walking wounded” and should be tagged later. Green patients should be directed to relocate to a casualty collection area (see figure 1, on page 14).

Dead or catastrophically injured are tagged BLACK. These patients cannot breathe after the airway is opened and are mortally wounded. The patients will probably die despite the best resuscitation efforts. It is often a difficult decision to leave a dying patient, especially if it is a child; resources should not be expended on unsalvageable victims.

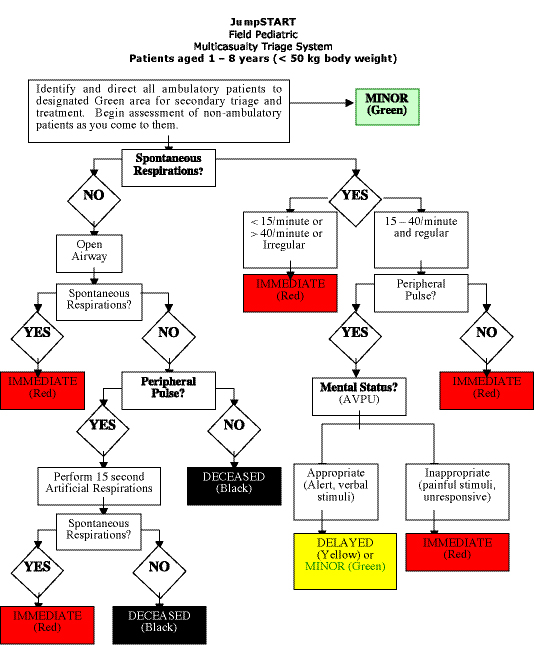

Triage for children: START is not appropriate for patients weighing less than 50 kg, as the physiologic criteria could result in under triage or over triage. Therefore, a separate system for the triage of children was developed by Dr. Lou Romig called JumpSTART. The JumpSTART system can be applied as an independent pediatric tool, or as a companion to START. The triage algorithm reflects a child’s increased likelihood of experiencing respiratory arrest without cardiac arrest. Such children may be readily saved if spontaneous respirations can be re-established promptly (see figure 2).

JumpSTART allows rescuers to give children additional chances while describing an objective point at which the system – not the rescuer – dictates that the child must be left for dead. Thus, the system promotes objective pediatric triage, assists in efficient resource allocation for all patients on the triage field, and provides emotional support for triage officers as they make the very tough but rapid decisions demanded of them.

As an emergency responder your first impulse will be to render aid to victims. The triage officer must resist this urge and focus on creating an organizational structure to help the casualties. As triage officer, your goal is to find RED patients. Your efforts should focus on locating all RED patients, getting them treated and transporting them as soon as possible. Once RED patients have been treated and transported, reassess all YELLOW patients and upgrade any to “RED-by-mechanism,” depending on their injury, age, medical history, etc. It is also appropriate to downgrade YELLOW patients to GREEN, when time allows, if on further assessment their presentation has improved.

When performing the triage function, regardless of incident size, don’t get distracted, move quickly and focus your attention on RED patients. Those are the real lives that can be saved. The goal is to stay focused on the RED patients. Most victims who have self-extricated themselves prior to EMS arrival can be labelled GREEN; all other patients will most likely be tagged RED, YELLOW or BLACK, depending on your START assessment.

Failure to use an organized approach to an MCI situation can result in an inappropriate use of vital resource, the failure to transport the most critically injured patients first, an incorrect approach to scene management where triage is based on emotion instead of objective criteria, the presence of victims on scene for extended periods of time, and worker dissatisfaction as the scene is chaotic instead of organized. Proper triage is a crucial step that helps prevent these problems from occurring.

Handling the MCI scene can be overwhelming for emergency responders. By having the proper procedures in place prior to the incident, many of the anticipated problems can hopefully be avoided. Creating order out of chaos is a difficult task, but tools such as START triage help make the rescuers’ job much easier.

Barry Bouwsema is a 20-year veteran with the fire service and works as a company officer/paramedic for Strathcona County Emergency Services in Sherwood Park, Alta.

Print this page