Features

What is resilience?

Defining a prevalent but elusive term in mental health

February 21, 2024

By Nick Halmasy, MACP, Registered Psychotherapist

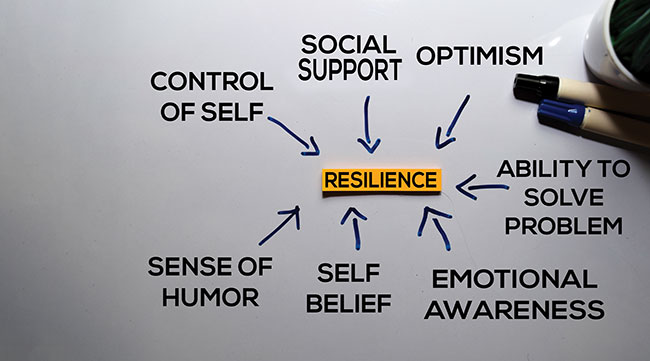

What ingredients create resiliency?

PHOTO: © syahrir maulana / iStock / Getty Images Plus

What ingredients create resiliency?

PHOTO: © syahrir maulana / iStock / Getty Images Plus What is resilience?

At first glance, resilience seems to be a fairly straightforward concept, but I had a strong suspicion otherwise. I asked a few friends, colleagues, and random people on the internet to define it and heard: “The ability to persevere through unknown hardship and to come out stronger.” “Maintaining forward momentum despite resistance and setbacks.” “You bend, but you don’t break.”

When talking with my psychotherapist friends, resilience got a bit more technical, but most answers landed around emotional regulating and coping, in whatever manner, to overcome a situation. Turn to the psychological research, and the nuances of defining resilience become more apparent. Gill Windle, in a 2010 article on resilience, wrote that “the complexities of defining what appears to be the relatively simple concept of resilience are widely recognized.” Phew, it’s not just me.

I came across a conference-based paper by five resiliency research juggernauts resulting in five different formulations of resilience. Resilience has even been defined as, more or less, “an empty word that can be filled with almost any meaning” (van Breda, 2018). In an article on resilience training versus psychoeducation, Jennifer Wild, a psychologist with Oxford, and her colleagues concluded, “Perhaps an operationaised definition of resilience is needed that allows an assessment of better than expected outcomes following stress exposure.” Things are not looking any clearer. Donald Roberston, author and psychotherapist, highlights this problem a bit more practically for us. He wrote that when building resilience, “there’s some ambiguity about what ‘adapting’ or ‘recovering’ mean insofar as there’s no set-in-stone definition of wellbeing.” When there is no common goal post to aim towards there is just wellness relative to the person measuring it. This in turn, makes researching it much more complicated and there are problems in the research we do have.

Catherine Panter-Brick identified some of the “deadly sins” as she cites them in resiliency research: being non-specific in defining it, being “empirically light” on researching it, and not being methodologically sound in how we go about the whole process. So, even in the research that we do have we need to be vigilant in our reading of it. George Bonnano adds to this list by identifying that we often use “retroactive” studies that ask those involved to recall their resilience. This is rife with its own issues. Identifying “prospective” studies is more likely to identify larger numbers of resilient individuals. The difficulty with this, of course, is that we would need departments to sign up prior (think recruits) and follow them through the course of their career (let me know if you’d be interested!). Dr. Sadbhb Joyce and colleagues also identified that a problem with the research is it heterogeneity, meaning that so much of the research is on such vastly different projects that it is difficult to pull them all together to get a cohesive story. It’s hard to measure resilience if all the programs are providing different trainings and different intervals and in different ways.

Similarly, we need to understand what type of resilience we mean. This, at least, is the easiest problem for us to solve. You won’t find me talking about children’s performance on math tests; performance following stressors, but about the absence, mitigation, or effective navigation of a psychiatric concern. This makes grouping all the research together to get a better idea of type more difficult because the studies are too heterogenous, meaning so vastly different in definition, methods, populations, etc., as to halt any meaningful conclusions. We have to, for now, stay in our own lane, but it’s also useful to purposefully narrowing our definition. We aren’t looking, necessarily, at all the ways someone can be resilient (van Breda, 2018).

We all tend to agree that being resilient exists. The conundrum lies in what exactly this thing is. Being able to identify resiliency more clearly would go a long way towards understanding why two people experience the same call and one may struggle while another would not. Unfortunately, the concepts on understanding this that we do have often fall into a camp that’s stigma laden and uninformed most of the time — a “can’t cut it” stance. In a better understanding we may be able to uncover the secret sauce of resilience making it more accessible to all our firefighters. Developing resilient practitioners would also lead to better outcomes.

One of the authors of “Developing Firefighter Resilience”, Dave Gillespie, discusses resilience from a sports psychology lens to develop resilient firefighters through the same principles that develop resilient athletes. There are important components here. Resiliency in high stress situations comes down to understanding and knowing your craft, yourself, and your physiology. The research tends to echo the sentiments that part of resilience can come from performing well under stressful circumstances. Marycatherine McDonald, PhD, writes in “Unbroken” that a portion of moral injury (associated with trauma) is feelings of incompetence. There is something to this automaticity of our role that can lead us to being a bit more rubber rather than glue.

A quick aside about what resilience isn’t seems also important here. Resilience (like any mental/physical health approach) does not mean that you will get to walk through life free from strife and sickness. No amount of resilient training is going to make hard times not hard. What resilience would be able to do, in the ways that we have conceptualized it, is to not make those moments worse. Indeed, resilience is also about enabling you to walk away from these situations without having made the problem bigger prior to you leaving. And this is a huge piece to try and understand. Sometimes, we find ourselves searching for the answer that will make things go away. Resilience is more along the lines of learning to live with this newly discovered cognitive roommate, while setting up effective barriers and boundaries to successful navigate when they are home and annoying us.

What the current research says

Current research does seem to land on some key resilience-trait properties. Taking some liberties, but in keeping with the wider literature, resilience, then, would be something like, the ability to continue to move, despite adversities, and while adhering to one’s values. That definition is specific enough to potentially measure while diverse enough to accommodate the obvious subjectivity of it all. Now that we know what it is (kind of)…where can I buy some?

Since I started After The Call, a resource centre for first responders, one of the biggest pieces of work was educational presentations and trainings. This was for entire departments as well as peer-teams and at conferences. The aim was that developing awareness and literacy around mental health could go a long way to preventing that what could be prevented and healing from that which could not. Not resilience in the specific sense, but resilience-adjacent in the common-sense of ‘knowledge is power.’ But swoop back in Oxford psychologist Wild: “We found no evidence of the effectiveness of pre-employment screening or psychoeducation offered as a standalone package, and little evidence for interventions aimed to improve wellbeing and resilience to stress…” Great.

This is an exceptionally important point considering that fire departments have PTSD prevention plans that include psychoeducation and training. Specifically, there have been many programs of “resilience” training, but by and large those don’t seem to plant the seed of resilience for us as much as we would have hoped.

Locally, we have some initial research that would suggest programs such as the Road to Mental Readiness, largely disseminated for the first responders, bring “no statistically significant changes in symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, posttraumatic stress, and alcohol use, at any follow-up time point, following the training intervention,” as Nicholas Carleton and his colleagues concluded – it’s not a treatment. Some small changes were seen in other measures that suggest these programs could be good for stigma fighting provided refreshers were given. The takeaway here is that psychoeducation alone is not resilience training (Wild et al., 2020). There is also still room for inviting someome like me into the department to talk about mental health, but we can no longer mistake it for anything other than basic information that will not go on to provide any real actionable help. It’s not a treatment. Can resiliency even be taught? You would think with all the hubbub above that the answer would be no. That is a bit hasty. Wild and colleagues do go on to identify that there may still be some areas for which resilience training is fruitful and beneficial. The problem with resilience training is that, by and large, it hasn’t focused on modifiable factors. What are things we can actually change? For example, if you come to see me for therapy, a modifiable factor for us could be your level of anxiety and it could be changed through different processes and tools that you learn to use and adopt (modifying your cognitive, behavioural, and emotional experiences). Psychoeducation feels a bit like that, but as has been argued elsewhere, being aware doesn’t make you literate. Sadbhb and her colleagues found that trainings that she has researched that focus on the cognitive behavioural and mindfulness approaches together “appear” to make increases in resilience.

The research would suggest that we need to offer a wider suite of tools. Mindfulness training is a great skill, but it is only one single skill. One tool is helpful, but a disaster if we rely only on it. Imagine coming to all MVC scenes with only a single tool every time. Even if 95 percent of the time they get us to the goal post, that five per cent is going to ache. It’s about having an adaptable and flexible skill set to employ the right tool for the right problem. Trainings haven’t seemed to focus on this too well. To be fair, and the research echoes this, there isn’t yet a ton of research studying the different trainings out there. Some preliminary research does suggest that some programs could provide that. One being utilizing the Unified Protocol (a specialized, transdiagnostic tool used to treatment anxiety and mood disorders, Wild et al., 2020). This is largely because the program itself is as much a training and therapeutic tool as it is for developing new cognitive skills. When using the program with clients and patients, I often tell them to look at this as a “cognitive lifestyle change.” That lifestyle change is based on modifiable factors that, when addressed, makes one better able and suited to adapt and take head-on the psychological trials they will face. I don’t presuppose that this is the only program suited to providing that, but it is one that arises in the research as a potential candidate. The number of appropriate coping strategies become almost infinity when we recognize that the only person able to gauge their effectiveness is the person using them. Developing a resilient firefighter through programming requires developing a large set of diverse skills that can be applied in many situations.

Addressing resilient versus not resilient

A hard and sensitive aspect of all this is who gets the star of resilience, and who doesn’t? This, inherently, doesn’t feel good. Who is resilient is the wrong question. It’s why were they resilient? And even more specifically, why now, in this moment. It’s unhelpful, unwise, and misinformed to suggest that when one of two people at the same call go on to struggle that they are less resilient than their colleague. This is simply a misnomer that continues to push the insidious stigma of “not strong enough”. In our effort to make sense of what is wildly difficult to make sense of, we’ve chosen the easy understanding. We work to “otherize” our colleagues. We question their leaves, or the amount of WSIB claims, or the number of times they need to head home. Yet, these are all viable options under the realm of ways to cope.

Organizationally, these options are difficult as they involve moving other parts around (some of those parts being people and they can be hard to find quickly in a pinch at times). But this would be to miss the point and to participate in the organizational contributions of the stress of the job. Research suggests that organizations that recognize, understand, and support in meaningful ways are also methods to decrease those leaves in the first place. And whether it’s a chicken or egg scenario, it’s never too late to adopt new ways of managing these pieces. Roberston poses a reasonable question: “Who is more resilient: someone who experiences no stress, no unpleasant experiences such as worry and anxiety, or someone who does feel stress but willingly accepts it and acts according to their values anyway?”

Ultimately, resilience will require one thing over everything else: Acceptance that we could be impacted. Resilience, as you have just read, is not the ability to withstand all assaults on our minds – that’s foolish to think in the long-term. Instead, its about how one manages that assault.

So, where do we stand on this resilience thing? Well, it’s a difficult to define a state of being that encapsulates something like moving forward in the face of adversity while maintaining your values. It will be a Swiss army knife of strategies and skills that will come together in a moment of need to help manage, moderate, mediate and potentially ameliorate the stressor at hand. Like most things, there is work to do to ensure that we develop the requisite skills for ourselves – and even better when the organization we’re with understands and values this enough to support you to develop them.

Nick Halmasy is a registered psychotherapist who spent a decade in the fire service. He is the founder of After the Call, an organization that provides first responders with mental health information. Contact him at nhalmasy@afterthecall.org.

Print this page