Features

Structural

Training

Handling highrises

Highrise buildings have long posed challenges for fire services. Although highrise fires are rare, these multi-storey buildings are complex structures. Highrise fires, therefore, demand large numbers of fire service personnel and pose occupant control and evacuation problems.

April 22, 2009

By Charles Jennings

|

|

| The city of Surrey, B.C., expects an increase in the numbers of highrise buildings over the next several years and has put in place a plan to deal with potential highrise fires.

|

Highrise buildings have long posed challenges for fire services. Although highrise fires are rare, these multi-storey buildings are complex structures. Highrise fires, therefore, demand large numbers of fire service personnel and pose occupant control and evacuation problems. In addition, many highrises have unique standpipe systems, which present water-supply and fire-attack challenges.

Incident command and communications challenges of highrise buildings are well documented, testing even the best accountability and communications protocols.

In short, highrise fires test almost all elements of the fire service, from inspectional services to dispatch and fire suppression activities.

Faced with a highrise building boom, the Surrey Fire Service in British Columbia began to question its ability to meet this growing and changing cityscape. While the fire service had made progressive changes – including the adoption of a shelter-in-place policy to manage the large numbers of occupants in these buildings and the requirement fire-safety plans by building owners – fire officers believed more should be done. (A shelter-in-place policy is designed to encourage building occupants who are not threatened by a fire to remain in their apartments or offices. Many deaths in highrise fires have occurred because occupants have left the relative safety of their units and were exposed to smoke or combustion products during their attempt to get out of the building.)

| The study approach The study took place in four phases. 1. Data collection a. local fire incident report statistics over almost 30 years b. local building use and count data c. B.C. fire incident data d. Summary U.S. fire data 2. Review of major highrise fires for lessons learned, and code approaches in other communities in North America. 3. Identification of local vulnerabilities based on steps one and two above, and resources available to the Surrey Fire Services. 4. Recommendations for improvement. |

Surrey, like many communities, had a relatively small number of highrise complexes – fewer than 25 when the study started – almost entirely residential. But the number of highrises will increase over the next five to 10 years and these new buildings will be taller and contain mixed uses, according to city plans and development plans already approved.

The initial approach to coping with this changing environment focused almost solely on upgrading the response to include more personnel. After members of the department informally surveyed other fire services, it was agreed that although this might be appropriate, there was vast divergence in response strength among peer departments. More needed to be done but it wasn’t clear what the next steps should be.

There were two camps: one wanted to throw everything the department had had at any highrise alarm; the other that felt that existing fire experience had been relatively good and that minor changes or no changes were needed.

The department hired a consultant to identify a plan for future highrise fires through international best practices and highrise fire experience. The consultant proposed a systems approach in which all major elements of the highrise problem be addressed simultaneously. To reflect the challenges unique to Surrey, the department’s own data was used, as were statistics and fire experience at the provincial and national levels. Case studies of large-loss highrise fires were also studied.

In the midst of the study, members of a highrise committee composed of firefighters, officers and administration met with the consultant to convey perceptions and concerns and review proposals and suggestions.

Staff in all areas of the department were interviewed and dispatching facilities and equipment were reviewed. Visits were made to select residential and commercial highrises, existing installations were reviewed and there were informal discussions with building staff.

The purpose of these visits was to gain an understanding of local perceptions and practices and to better appreciate the operating environment. These visits were very useful in breaking through some of the perceived silos in terms of suppression versus prevention and headquarters versus line companies. For example, headquarters felt strongly that the onus for inspection of new protective systems in highrise buildings fell squarely on the owners or their third-party experts. A concern about reducing the inspectional burden on fire prevention personnel was perceived by suppression personnel as a snub – they felt they were being left out of the loop on new construction within their service territory.

Similarly, all elements of the fire services may not have fully appreciated the contribution of non-suppression personnel to dealing with the problem and the ongoing efforts necessary to lobby for code changes at the provincial level.

■ The systems approach

Based on the review of fire experience – successes and large-loss fires – it was found that there were three elements that were critical to successfully manage a highrise incident:

- Building construction/code enforcement;

- Public education;

- Fire suppression.

When any of these areas is neglected or insufficient, the potential for large losses increases. Importantly, after-action reviews of major incidents reinforced the notion that each of these areas must be supported through sustained effort. Good programs and policies must be kept in force and not left to wither as organizational attention moves to other issues.

Using previous research, a conceptual model of fire incidence and fire loss was used to illustrate the need for attention to multiple dimensions of the fire problem. This model stated that in order to understand fire loss we must consider characteristics of the building stock (size, egress capacity, protective systems), occupants (number, age, impairments) and fire-service response.

■ Qualitative findings

Significant highrise fires were relatively infrequent events in Surrey, as they are generally. Because of this, past success could not be clearly attributed to design. As mentioned, there was a relatively small number of existing residential highrise buildings but many more were under construction or in planning stages.

Given these conditions, actions now would set the stage for a new generation of highrise buildings and these decisions would be felt far into the future.

A review of local fire data over 20 years revealed several interesting facts about highrise fires in Surrey. The number of highrise fires has increased over the past nine years, averaging about five a year. This number is expected to increase as more highrise buildings come online.

The majority of highrise fires occurred in residential buildings; further analysis showed that there was an injury rate of 0.1 per fire in both highrise and non-highrise buildings.

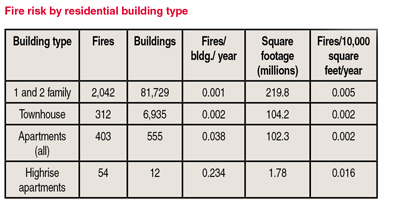

Data on building characteristics (number, use, and square footage) was used to gain a better understanding of fire risk. Using these data allowed fire risk to be calculated on a per building and per square foot basis. The analysis of fire risk in Surrey using this data is shown the table below.

|

|

| VIEW LARGER

|

Viewing fire risk on this basis provide a new perspective on assessing relative safety and for targeting prevention programs and possible building or fire code changes to reduce the number

and consequences of fires. For example, fires per building might be useful for targeting code interventions and inspections whereas fires on a square-foot basis might be more appropriate for targeting public fire education.

Of interest from this analysis is that a fire in highrise building is expected roughly once every four years, while a fire in a single family dwelling is a much rarer event, on the order of one in 1,000 for any particular house in a particular year.

An additional analysis looked at the role of detection and suppression systems in fires. Generally, it is expected that highrise buildings would have a higher rate of working smoke detectors or suppression systems. Most tellingly, there were no smoke detectors installed in five per cent of highrise incidents versus 30 per cent for non-highrise buildings. Overall, smoke detectors activated in 64 per cent of highrise fires, as opposed to 17 per cent of non-highrise buildings. This reflects code compliance that exists for highrise buildings.

|

|

| VIEW LARGER

|

Interestingly, smoke detectors sounded but occupants were unable to react in 28 percent of highrise incidents versus fewer than one per cent of incidents in the non-highrise buildings. This my be explained by the presence of smoke detectors in highrise occupancies including hospitals but also indicates that vulnerable populations may be more likely to be found in highrise buildings. This has some important implications for pre-emergency planning and incident response and is worthy of further exploration.

Sixty-one per cent of highrise buildings in the fire reports were equipped with complete sprinkler systems versus just 4.9 per cent of non-highrise buildings experiencing fires.

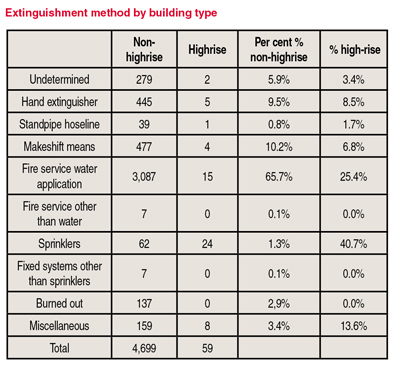

The effects of sprinkler systems on fire service activity at highrise fires were an other notable finding. Sprinklers extinguished almost 41 per cent of highrise fires and fire service hoselines were used in 25 per cent of highrise fires. In non-highrises, hoselines extinguished 66 per cent of fires. The difference in hoseline use corresponds almost exactly to the presence of sprinkler systems.

■ Conclusions

Departments will never get ahead of the highrise problem with staffing and response alone. Even the largest and best-equipped departments can commit hundreds of personnel to a significant fire and even the largest fire services have had poor outcomes in spite of their abilities to respond in force.

Working with its own data, the City of Surrey has created a defensible, multi-faceted approach to the highrise problem that has inspired buy-in from all elements of the department. The effort will require immediate and long-term actions by many parts of the fire service. These efforts position the Surrey Fire Service to address its future needs while improving the state of fire safety in highrise buildings now and into the future. Many of the findings of the study could be applicable to other departments.

Charles Jennings, PhD, MIFireE, is principal consultant for Manitou, Inc., a public safety consulting firm in New York state. He is on the faculty of John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Len Garis, the fire chief in Surrey, worked with Jennings. He has undertaken extensive training in the fire fighting and emergency response sector and has completed more than 30 courses through organizations including the Justice Institute of B.C., Office of the Fire Commissioner, RCMP, University of B.C. and the Canadian Emergency Preparedness College. Garis frequently shares his expertise through written reports and presentations, by serving in an advisory capacity and by providing expert testimony in the courts.

| Recommendations

■ Dispatch and communications

■ Fire suppression

■ Codes and enforcement

■ Public education

■ Training and mutual aid

|

Print this page