Features

Trainer’s Corner: Mastering arrival reports

March 18, 2024

By

Ed Brouwer

The first radio report to dispatch is a “through the windshield” report. .

PHOTO: © davidfillion / iStock / Getty Images Plus

The first radio report to dispatch is a “through the windshield” report. .

PHOTO: © davidfillion / iStock / Getty Images Plus In most volunteer/paid-on-call departments, rookie training is well underway. By now you have likely completed communications and alarms. Pretty boring stuff, especially when that new recruit is itching to get to the fire behaviour portion.

Years ago, I transferred the information regarding communications and alarms found in the “Canadian Firefighter’s Handbook” and the “IFSTA Essentials of Firefighting Manual”, to PowerPoint. During our first presentation, I noticed the firefighters’ interest peaked when I showed the last few slides. At first, I thought it was because the end was near. But no, it was the few lines about arrival reports that hooked the attention of the rookies and our veterans (we trained together).

If you have been training for any length of time, you realize just how important it is to find those often-rare points of engagement. So, at the following practice I skipped right through the 40-plus pages on communications and alarms to the two small paragraphs pertaining to arrival reports, aka initial reports.

We spent the whole practice doing arrival reports. Yes “doing.” I turned a written description into a hands-on training session. The interaction was very enthusiastic.

It was quite simple really. But before you present this to your members, you must ensure you thoroughly understand what an arrival report is.

Key #1: The first radio report to dispatch is known as the arrival report. The first arriving fire officer makes it, while he or she is still in the apparatus.

This is a “through the windshield” incident report. To be effective, this report needs to be clear, concise, and relevant.

It should include: “On scene” confirmation, incident location, building construction, fire conditions and the establishment of command. It should also include all obvious hazards, such as downed power lines, critical exposures, visible propane tanks, or any other critical safety information.

Key #2: “On scene” indicates that command has been established and confirms the location of the emergency.

There may be times when the address given is wrong and the first first-arriving officer can correct that. Accurately determining the incident location can affect arrival routes of other responders and apparatus placement. Occupancies that are well known to all the incident responders should be simply identified by name.

Key #3: The first-arriving officer should identify the fire building’s construction type. This gives the other responding units an idea of what actions they can expect to perform based on the differences of fire behaviour in that construction style.

The first arriving officer plays a very vital role at the front end of fire ground operations.

Key #4: The initial report although it may be all of a 30-second time investment, pays huge organizational dividends, leading to more efficient and safer outcomes.

There are no “do over” options. If the initial IC does not spend the few seconds required to organize the initial attack it is going to take a whole lot longer to play catch up.

Key #5: The IC also has the option of changing the response mode of responding resources. If he gets on scene with “nothing showing,” he can choose to have other responders Stand Down or continue in Code Two.

Several years ago, we were the second unit out to a multiple vehicle pile-up. Most of us were in our quiet place wondering what we would arrive at. Was it one of our neighbours or a family member? I remember the audible sigh of relief that came when we heard that our rescue unit was on scene of a multiple MVI, and that no extrication was required. Dispatch told us to continue Code Two.

Note: This type of notification is extremely important for those departments that still respond to incidents in their personal vehicles.

Key #6: When describing conditions, the first arriving officer should paint a clear picture for incoming units. How much smoke and/or fire do you have?

Where specifically is the fire? This mental image you are painting can be useful to incoming units.

Consider: “We have heavy black smoke showing from the first floor, Alpha/ Bravo corner.” Or “We have a fire at 1123 Main Street.” The second statement tells us little if anything that we did not already know. And that is the point of the arrival report — to tell us something that we do not already know.

It may help to let dispatch and the other responders know what operational mode you are starting out in — offensive, defensive, investigative, or rescue.

There is also an opportunity to get help coming right away, the arrival report can include a request for a second/third page, mutual aid, hazmat, forestry, RCMP, EHS, or utilities. It is easier to cancel a request then to get it last minute.

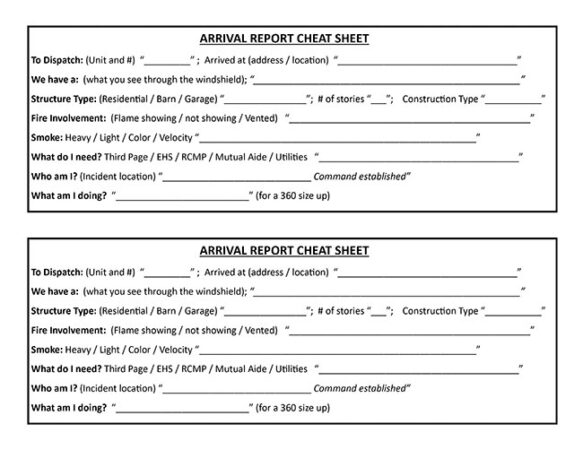

This Arrival Report “cheat sheet ”is printed on index cards and placed on the sun visors in each unit.

PHOTO: Ed Brouwer

Key #7: Establishing command lets everyone know who is in charge (command can be transferred as the incident evolves). The first arriving officer is the IC until further notice. Command is described by location not firefighter’s name, so if your incident was located at 83 Maple Ave. you would say, “Maple Ave. Command established.”

Key #8: Now that your 30-second through the windshield report is complete, it is time to do a more detailed size-up. You must get out of the apparatus to do that, so you notify dispatch that you are going mobile. The notification that “command is going mobile,” lets everyone know the IC is doing a more detailed size-up and that a more detailed report is coming.

Good on scene reports don’t just happen. The worst place to learn how to give an on-scene report is in front of a burning building. Do keep in mind that the initial on scene report should be short, sweet and to the point.

The more these arrival reports are practiced, the better they will become (getting shorter while conveying more critical information).

Although there are only two small paragraphs dedicated to arrival reports in the chapters relating to communications and alarms, this is where most successful outcomes are achieved. The first five minutes sets the stage for the next five hours.

In the image accompanying this article, you’ll see a copy of our arrival report “cheat sheet.” This is printed on index cards and placed on the sun visors in each unit.

For our practice I prepared multiple PowerPoint slides showing scenes of structure fires, MVIs, and even a few buildings with no fire or smoke showing. Each slide had a local address typed at the bottom.

Our members, each with arrival report “cheat sheets,” were seated in a semi-circle facing the screen where I projected these pictures. As a slide came up firefighters (taking turns) were to pretend to be the first arriving officer.

The picture was what they saw through the windshield of their unit.

We then asked them to use the handheld radio to report to our “in house” dispatch an arrival report.

Point of interest: When I showed a picture of several first responder units (RCMP, EHS) parked on the side of the road, no visible fire, smoke or MVI, the firefighter giving the report stalled. He started to describe what “he thought was going on,” but then gave up.

This provided a profitable brainstorming session. There was lots of interaction that led to discussions on fire behaviour, fire suppression tactics and strategies, firefighter safety and observation skills. There is a bit more to this topic, but this is certainly a good start. I hope this info will help your members give solid arrival reports that lead to successful fire operations. I encourage you to practice, practice and practice doing arrival reports – do it until it becomes a habit. In the meantime, please stay safe, and remember to train like lives depend on it, because it does. 4-9-4 Ed

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., a retired deputy chief training officer, fire warden, WUI instructor and ordained disaster-response chaplain. Contact aka-opa@hotmail.com.

Print this page

Advertisement

- Winnipeg firefighters battle two blazes on Saturday

- Former Calgary Fire Chief Bruce Burrell dies at 65