Features

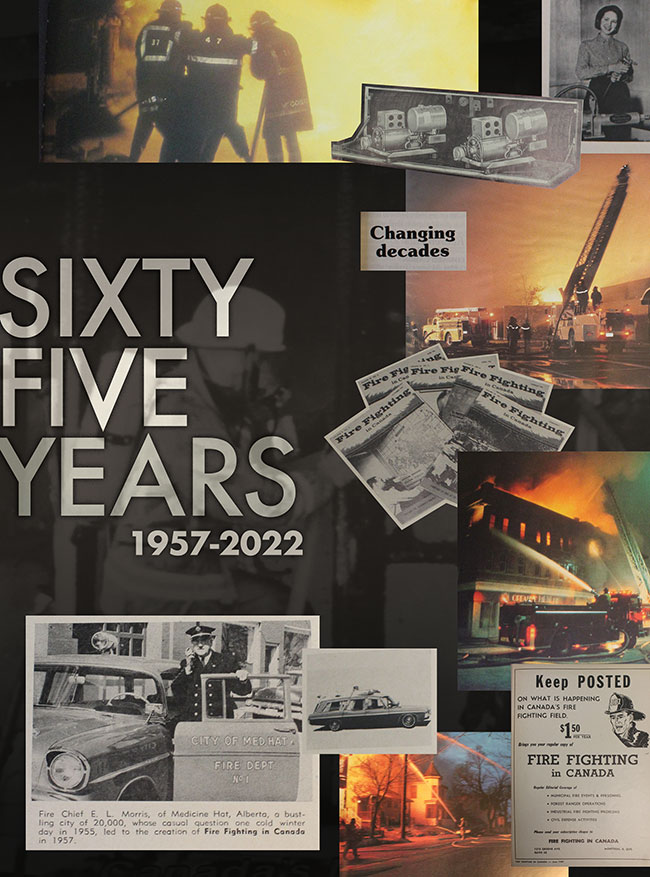

65 years

Business has changed. The fire service has changed. Hear from some familiar names in Fire on the way we were.

August 19, 2022

By

Laura Aiken

Writing about the past is like tugging at a magician’s scarf; no end to the next colour, each piece of fabric leading endlessly to another. The future is such a mystery that a speculative piece is pretty tidy to package up by comparison. For Fire Fighting in Canada’s 65th anniversary cover feature, I tugged at the magician’s scarf and chose a sampling of the colourful history of the fire service and industry, by no means comprehensive, and certainly inspiring a second flip through the Rolodex to share more in a future issue.

Canada has a lot to be proud of with so many long-standing companies still thriving. The late Alfred Joseph Stone spent years in the manufacturing and sales side of Fire before starting Ontario-based A.J. Stone Company in 1972. Commercial Emergency Equipment’s history stretches back to 1947 in Vancouver.

The history of Canada’s fire apparatus is a storied one, and a legendary piece of the fabric began with Charles Thibault and Pierre Thibault Ltd., in Pierreville, Que., circa 1918. Thibault was one of the best known and biggest apparatus manufacturers for much of the 20th century, with the original company intact until 1989. When World War II broke out, Thibault was awarded multiple contracts from the Canadian government that helped propel the company towards expansion, detail authors Bob Dubbert, Shane MacKichan and Joel Gebet in the Encyclopedia of Canadian Fire Apparatus, which shares the story of this iconic Canadian company amongst many others. The Encyclopedia of Canadian Fire Apparatus was published in 2004. At that time, 17 of the manufacturers in the book were still operating. Twenty-four were out of business. Some of the bigger names no longer around, like Bickle and King-Seagrave, will still ring bells. Some, like Fort Garry Fire Trucks (born 1979), Dependable (born 1975), and HUB Fire Engines (born 1959), are old-era institutions that continue to innovate and succeed today.

Thibault, who introduced many innovations in the aerial market, debuted his first custom cab-forward fire truck in 1957 and died n 1961, leaving behind nine sons fraught with infighting and power struggles — Pierre-Paul, René, Julien, Charles-Étienne, Gilles, Marion, Yvon, Réjean and Guy — some of whom would go on to make their own marks on Canada’s apparatus industry. In 1968, five of the nine sons left to create their own company, Pierreville Fire Trucks, putting the two factions in competition with one another. Thibault continued to be successful, expanding its fire truck exports into America and beyond.Despite these successes, Thibault declared bankruptcy twice – in 1972 and again in 1979. Pierreville filed for bankruptcy in 1985. Thibault filed for bankruptcy a final time in 1989, but the business innovations were purchased by a group of investors lead by a former executive of Bombardier, who formed Nova Quintech (1990-1997). Pierce Manufacturing bought the rights to Nova Quintech’s aerial line of product in 1997. The Thibault’s are still around the fire industry in various business enterprises, including Carl Thibault Emergency Vehicles and C.E.T. Fire Pumps Mfg. The historical details were summarized from the Encyclopedia of Canadian Fire Apparatus.

John Witt began working for Pierreville Fire Trucks in 1980 as their sales manager. Having sold himself into retirement at the age of 28 after his first ventures, Witt put his salesmanship to good use for five years with the storied Quebec apparatus maker. One of his key later contributions for fire departments was engineering the arrival of Bronto Skylift to North America in 1985; helping pioneer Bronto as a leader in advanced articulating and high reaching aerial devices. In 1993, he entered the market as a dealer by starting Safetek Emergency Vehicles Ltd. and later purchased Profire Emergency Inc., to create what is now known in the industry as Safetek Profire, one of Canada’s leading providers of fire-rescue vehicles, parts and service.

After 42 years serving fire departments, Witt said there’s nothing he would have done differently; it’s been a business life of no regrets and many pluses.

“I’ve also been very fortunate to get to know and become friends with competitors and associates through the NFPA 1901 Apparatus Committee which I served on as the only Canadian member for a number of years and now currently on the ULC S-515 Apparatus Standards Committee…I’m proud to see the apparatus we’ve sold save lives and property. I’m proud to see the products and services that we’ve provided to our customer help save lives and property. Our team shares my passion and supports our mission of “Serving Those Who Keep Our Communities Safe.”

A lot has changed since the days of Pierreville when Witt could just price out a truck with a few basics on a piece of paper. Now, sophisticated software creates specifications and line item pricing. A tender used to be 10 pages, now they’re up to 200 with all the specs, legal requirements, terms, and conditions. He’s now also seeing fire departments use group (cooperative) purchasing and long term contracts/agreements to help standardize apparatus and reduce the need to re-tender every year, which expedites the process and is expedient and transparent.

A lot has changed since the days of Pierreville when Witt could just price out a truck with a few basics on a piece of paper. Now, sophisticated software creates specifications and line item pricing. A tender used to be 10 pages, now they’re up to 200 with all the specs, legal requirements, terms, and conditions. He’s now also seeing fire departments use group (cooperative) purchasing and long term contracts/agreements to help standardize apparatus and reduce the need to re-tender every year, which expedites the process and is expedient and transparent.

Also, the sales cycle is longer today. It used to take fewer than 365 days to build a fire apparatus. Now in some cases, and with some builders, 18 to 24 months or longer is the norm. “And I don’t think that’s going to change in the near future,” he said. “We’re suggesting departments expedite their process and consider purchasing apparatus already in production — or stock units.” Stock or not, the life cycle of fire apparatus purchasing has become more complicated and expensive. Inflation can mean significant budgeting increases, primarily due to supply chain issues. A city budgeting to replace an apparatus in 2022/2023 for a delivery in 2024/2025, will need to factor in significant cost increases.

When asked what his workday was like in, say, 1989, compared to today, he said “personal contact” was one of the most prominent methods of securing a sale. “Now we’re using emails and phone or Zoom calls.” He recalled a story where a new deputy was hired by a suburban Toronto area FD and was told by the fire chief to purchase a new aerial apparatus. So he called around and said ‘who do you talk to?’ He was told to call John Witt, the ‘Aerial guy’.

“He called me out of the blue. I flew to Toronto to see him, told him the features and advantages of my apparatus and he bought it.”

He said it was the sales person’s knowledge/expertise that gave him both the confidence and comfort in what he was purchasing. That was biggest factor in closing the deal of yesteryear. However, despite all of these changes and challenges, this remains a relationship-based industry.

Witt and the Safetek sales team travelled more in the past, spending time taking customers to the factory for pre-construction, pre-paint and final inspections. Now much of that is done remotely. The benefits he sees are the reduced costs and less time away from family for everyone, but as a relationship builder, he says he does miss spending time with established and prospective customers. He much prefers face-to-face interactions to doing things by Zoom: “You can’t always think of everything over a Zoom call.”

Apparatus was simple when Witt started; electronics weren’t even on the market and he has seen technology go from fairly basic to highly technical and sophisticated. “You’re getting apparatus that can be run on your phone now, so to speak, and not everyone is ready for that level of sophistication.”

Apparatus technology has changed and so has fire service purchasing structure. One trend sees the city’s finance or purchasing departments more heavily involved in the acquisition of fire apparatus because of the capital nature. This requires cooperation and insight on both sides so the FD can acquire the apparatus that they require for their specific operations at a justifiable cost. “Succession planning and training is going to be more important than ever. When the senior staff associated with apparatus and maintenance in a larger city retires, the wealth of knowledge and first hand experience has the potential of being lost.”

No more riding on the tail board. Rick Suche counts a fully enclosed cab as one of the biggest fire safety advances in his time. Image: © CSA Images / getty images

Rick Suche, president of Fort Garry Fire Trucks, is another long-time memory keeper in Canada’s fire industry. Suche started with Fort Garry in 1979 when they were building tankers for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Fort Garry was a general bodybuilder at the time, not yet specialized in fire trucks, and building two to five tankers a year. He had an interest in the fire service, so he took one of the tankers on a road show. They took the feedback, built a better one and the story snowballs from there. Fort Garry builds well over 100 fire trucks a year now. His said day has changed a lot simply because they are serving a lot more customers now with customers in frequently through the week.

Fort Garry moved into the a new custom built building in 2013 and the staff had a lot of input, which Suche counts as a major accomplishment and highlight for Fort Garry. The chiefs that come through the doors these days are more informed, he said, but since most chiefs only buy one or two trucks in their time as a chief, there is a learning curve and Fort Garry does a lot of educating on what’s available. The most important meeting is pre-production —that makes for a good final inspection — and he said that aspect hasn’t changed over time.

Suche likes to maintain face-to-face interactions, ensuring customers are well looked after when they come to Winnipeg.

“They become part of our family. They become friends and many of my friends are long serving fire people as well as the support people and our suppliers.”

While face-to-face may be among the most un-changing, cherished preferences in business relationships, Suche has certainly seen much change. Forty years ago, change was resisted a lot more and was very hard to do, he said. Change is accepted faster now than it used to be. He pointed to the “Everyone Goes Home” campaign started in 2004 as helping change the conversation around firefighter safety, and now the cancer and mental health awareness have become evolving pieces as well.

“It hasn’t changed totally, but it is changing. Definitely.”

The biggest game changer he’s seen in all innovations was the safety of a fully enclosed cab.

“When I started, they were still riding on the tail board. Then they went to open cabs. Then they went to fully enclosed cabs. That’s the biggest safety feature…it saved the most lives.”

But the biggest change of his over four decades in Fire?

“Inflation was normally two, max four per cent a year. Now it 15 to 20 per cent on fire trucks. The chassis costs have just gone crazy. Completely crazy. That’s the biggest thing in 43 years that I can say I have ever seen – the price of fire trucks rise as fast as they have in the last two years. It’s an entirely different world we live in with the supply chain right now.”

Is it fair to say times were more predictable when we were waiting around by the phone instead of for parts to build the truck?

“You spent all day on the telephone and waiting for the mail to come in,” says Suche of his old communication toolbox. “I remember watching the first fax come in. That was an amazing thing to see back then.”

Fax seemed like an antiquated technology until I got on the phone with Brian Evans, a 73-year-old 50-year veteran of the fire industry and owner of Fides Novus Marketing, and he starting talking about telex. Telex used teleprinters and telegraph-grade connecting circuits for two-way based text messages between businesses in the post World War II era (and there it is, the original human propensity to text). Evans would type his message into a typewriter pad on the telex machine and it would be typed out on the other end.

“It was magic at the time,” he said. He also noted he paid two thousand dollars for his first cell phone (I suppose we can be thankful not everything has gone up in cost over the years). He paid the hefty price tag because if he was going to be late seeing a customer, he’d have to stop at a pay phone and spend 10 minutes telling the person he was going to be 15 minutes late.

“The battery operated one was all battery and looked like a construction worker’s lunchbox. I used to write my customer’s letters — write or dictate to a secretary and mail it away. Send it away with literature. You could be reluctant to call because long distance used to be expensive, and your boss didn’t want you to eat up too much long distance. Or you drove to see your customers. You training was: Here’s your keys, catalog, and cards. Off you go.”

In 1970, prior to starting Fides Novus, a marketing company that represents Hale, Federal Signal, Akron Brass and Snap-Tite Hose, among others, he took a job as a salesman at a company called Safety Supply Canada.

“The first time I sold a Scott air pack in 1970, I sold it with the cylinder for $350.”

He also sold a wool, long firefighter’s coat that came below the knees for about $100. The knee-length firefighter’s boots, just rubber boots, no steel toe, would run his customers about $17. Then, they would don thick wool mitts in winter or summer, dipped in a bucket of water.

“They kept your hands warm in the winter even though they were wet…it was weird stuff.”

Evans worked for Fleck Brothers after Safety Supply Canada, then went to Niedner. He stayed with them for six years, moved to corporate side, found it wasn’t for him so he started his marketing company, which he’s been doing for 35 years. He’s been travelling for 50 years, and time hasn’t changed that. In the first seven weeks of 2022 he hit up every province in Canada. I suspect 50 years of friendships coast to coast makes for particularly rewarding road trips.

“The thing that makes this business good is that the end users are good. Firefighters care. Fire chiefs care. Fire departments care.”

Will Brooks, co-founder of the Canadian Fallen Firefighters Foundation, in a vintage fire truck.

And, most definitely, Will Brooks in Lunenberg, N.S., cares. This 80-year-old has been keen on helping out in fire halls since he was a young lad. Brooks keeps a vintage fire collection through Lorne Street Fire Company and nationally he is known as a co-founder of the Canadian Fallen Firefighters Foundation. Whenever I call, he seems to have a finger on the pulse of anything from cancer coverage for firefighters to safety legislation. He asked me recently what I thought of Hebbville FD’s unique aerial on a smaller chassis for shorter buildings that was displayed at the Atlantic Fire Leadership Conference this year, noting it was a pet project of his to see it in Nova Scotia after seeing a similar truck in Italy about 20 years ago. Of pet projects, this man has many.

A fire truck buff at heart, his first memory jogged during our conversation is the 1948 700 series American-LaFrance pumper, which revolutionized design by having the motor placed behind the front axle.

“It changed everything, and I was born before that, so I remember the transition from that style to the 700 series.”

Brooks was raised in a tiny town in Maine (although he is Canadian), where his father was on the town council, and considered the “head select man,” which was the terminology at the time used to describe the leader of the town government. His father recognized his interest in fire engines, and took him to the station, which Brooks described as the corner of a garage, and he was able to sit in the apparatus. He recalled hearing the horn blow many times to send the alarm out and later on you’d find out where the fire was from a little sheet in the newspaper. His father kept his son alerted to active fires so he could go to see the fire trucks. The family moved to another small town in Maine, and through high school he was part of the fire department driving fire trucks and running pumps. At the time, it was commonplace for students to start the initial fire fighting and the older men, who were working in the day, to arrive later.

One story he remembers vividly. When he was nine, his father was ill and asked his son if he’d go down to the factory to pick up his paycheque for him. Happily, he went to the factory, which was across from the firehouse. He went in to get his father’s paycheque and when he came out the hand rung bell was ringing to indicate a fire in town. Brooks, feeling lazy, figured he could hitch a ride on the fire truck and get home a little sooner. He piled in as the truck zipped off, shaking with terror and clinging to his dad’s cheque as he realized the location of the fire required traversing an extremely steep hill by his school that would mean certain death should the brakes fail (he’d overhead the firefighters talking about it). The crew and their nine-year-old ride-along made it down the hill to find a small fire. Brooks grabbed a little broom from the truck (already knowing where everything was), and he went and beat the fire out. When more older men arrived, mystified to find a nine-year-old tamping out the fire, the man who brought him down in the truck said, “Oh, he’s no problem.” And that’s how he fought his first fire.

Brooks continued to go to fires, priming his interest in tactics and feeding his interest. He then went to university with no time for fire fighting or observing so much anymore, but he helped out the fire department during the summer when he was home, cleaning equipment and pitching in. He came to Canada in 1969 and worked full-time at a college doing counselling, and he didn’t think it wise to jump up and leave his patients when the pager went off. But when he went into private practice, he had more control over his time. At the age of 45, he joined the fire department and went to a fire school. When he started, he was given a “sort of duck coat” that two or three others had worn before, he said, and woolen mittens.

“And they gave me a helmet and the helmet was made of plastic and I was always very happy no one hit me over the head with it on.”

He joined another department in Nova Scotia and eventually retired at age 70. Since he’s been in Lunenberg he’s been continuously involved in the foundation, on the board of the Nova Scotia firefighter’s school, and just helped establish the Benevolent Fund. Retirement isn’t quite a word to hit Brooks’ vocabulary yet.

And on the west coast, Len Garis has taken a similarly non-retirement approach to his 2019 retirement from the helm of Surrey Fire Services. Garis was highly involved in the fire service during his 18 years as Surrey’s chief, and 39 in the service. He was a president for the Fire Chiefs’ Association of British Columbia and served on various committees addressing everything from building safety to injuries, receiving a number of honours and recognition over the years. He also pursued academic work as an associate, adjunct professor and instructor at various times. Post-retirement, he’s now the director of research for the National Indigenous Fire Safety Council and an advisor for the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics for StatsCan.

Garis got started as a volunteer firefighter by talking to a neighbour over the back fence, who happened to be doing recruiting for Pitt Meadows FD in August 1980. His foray into fire fighting looked very different than firefighters experience today.

“I showed up on a Tuesday, chatted with the chief. The chief gave us a number, showed us the hook for our hat and boots and said if the pager goes off come to the fire hall as fast you can. And don’t drive right away until you’ve had some practice. First call was a car fire, and I went to the fire hall and just waited in the passenger seat of the fire truck for someone to show up.”

He recalls the enormously social nature of the fire hall at that time.

“In my day, there was a beer fridge. It was a place to go. It had a lot of bravado and privilege in the membership and respect from the community. You needed people to follow and to create that environment where they wanted to belong when they had another job and families – you had to balance that. It’s a bit of an art to keep that in check.”

Today, the fire service still strives for that balance and struggles with recruitment and retention amongst its volunteers.

Another thing that has remained constant around the fire hall?

“The DNA of a firefighter — being focused on being ready; always being ready.”

A tale in longevity: Niedner, est. 1895

Niedner started making linen fire hose in 1895 in Massachusetts. The company, now making circular woven hose products in Montreal, has been innovating ever since, with the latest solution coming in the form of their Altra 3D two-in-one hose. The double jacket design is unique in bringing the outside and inside jacket into a single layer, eliminating snaking and wrinkling. One-hundred and twenty-seven years is a long time to hone your craft, and over the years Niedner was the first to manufacturer a lightweight hose for the fire service in 1982, and the first to make a circular loom for structural jackets larger than 12 inches in diameter in 2014.

Niedner started making linen fire hose in 1895 in Massachusetts. The company, now making circular woven hose products in Montreal, has been innovating ever since, with the latest solution coming in the form of their Altra 3D two-in-one hose. The double jacket design is unique in bringing the outside and inside jacket into a single layer, eliminating snaking and wrinkling. One-hundred and twenty-seven years is a long time to hone your craft, and over the years Niedner was the first to manufacturer a lightweight hose for the fire service in 1982, and the first to make a circular loom for structural jackets larger than 12 inches in diameter in 2014.

Anderson’s Engineering: 1972 – 2000

Duncan Anderson, owner and operator of Anderson’s Engineering, founded his company from the roots of his father’s machine shop in 1970. That same year, he built his first fire truck for the Langley Township Fire Department.

Anderson’s interest to the fire service started in the middle of his adolescence. Growing up in rural Langley, B.C., Anderson found himself going to the volunteer fire department.

“I couldn’t get a ride to the soccer field or baseball diamond or even to the movie theatres. The department was about a half mile away from my house, and I’d always been interested in cars and machines because of my dad,” said Anderson.

Anderson would later spend his 44-year career at the Langley department, seeing it transition from volunteer department to paid on-call to composite, and serving as district chief and deputy chief.

Anderson’s Engineering came about as a result of Anderson’s childhood fascinations and the chance to carry on his father’s business in his own way.

“When I built my first fire truck, a tanker, I took an old truck and built a new tank for the back,” said Anderson. “It worked very well but it was crude. The first truck I built with the help of a team was in 1974.”

Anderson’s Engineering went on to build apparatus for departments internationally and across Canada.

“We started out with one truck at Langley and next thing we knew, we were building trucks for cities like Seattle, New Jersey and later places like Puerto Rico, Guam and Saipan,” said Anderson. “We had a large number of trucks around B.C., Ontario and Quebec, too.”

In 1986, Anderson’s Engineering became a distributor for Bronto Skylift, which led to a number of Skylifts with Anderson bodies being delivered to departments across Canada.

“I remember when Montreal ordered the 50-metre unit, it was the tallest in North America at the time. That was a big moment for us,” said Anderson.

Anderson’s Engineering apparatus were built based on the need to departments.

“Being in the service myself, I knew that having a truck that worked for a specific departments’ needs were crucial,” said Anderson.

Anderson’s Engineering designed a number of innovative approaches to apparatus construction, including overhead ladder racks, transverse hose beds, separate pump compartments from the body and more.

Anderson said that while the growth and success of his business were impressive, he was proud of more than just the trucks they produced.

“I am exceptionally proud of the trucks we built, but I’m proudest of the people I had working for me,” said Anderson. “I designed the trucks and gave the guidance on how to build them. They were all great at what they did and great to work with too.”

Anderson’s Engineering closed its operation in 2000 but some of the truck built by the company are still functioning in smaller, rural departments today.

– Kaitlin Secord

Print this page