Features

Cancer in firefighters

Part 2 - The ancient discipline of fire fighting medicine

February 4, 2020

By Dr. Kenneth Kunz

Many young chimney sweeps, like the young boy picture here (circa 1877), were victims of a well-documented and savage cancer that was frequently fatal.

Many young chimney sweeps, like the young boy picture here (circa 1877), were victims of a well-documented and savage cancer that was frequently fatal. Editor’s Note: Part 1 in our cancer in firefighters ran in our December edition. In Part 2, we’ll be looking at medicine and disease in ancient firefighters. Look for Part 3 in March. Dr. Kenneth Kunz is a medical oncologist who has taken action in the fight against cancer in firefighters through visiting fire departments and spreading the message of risk in various ways. Dr. Kunz has written this three-part series with the support of the Fire Chiefs’ Association of British Columbia.

What I find thought provoking, as a physician who works with firefighters, is that overseeing the health care of each of the seven municipal fire authorities in imperial Rome was a team of four full-time physicians, in addition to a fire department chaplain, whose responsibility was to address the emotional, psychological, and spiritual needs of the firefighters. In other words, 2000 years ago, the professional fire rescue services of The Eternal City were staffed by a multidisciplinary health care team of 28 medical doctors, in conjunction with counselling and solace provided by a set of spiritual advisors. Aside from the well-known battlefield surgeons of the day, this, to my knowledge, may constitute one of the first subspecialty medical practices — Interdisciplinary Firefighting Medicine.

The necessity of such robust medical, psychological, and spiritual support in the fire service leads me to ponder certain questions as they concern workplace safety and health — including the mental health of Roman firefighters. What kinds of illnesses, injuries, and deaths were these ancient firefighters subjected to? I can find nothing mentioned regarding bunker gear or breathing apparatus in the historical reports —what kind of personal protective equipment was available to the fire service? One can imagine these staunch gladiators of the fire fighting arena battling burning apartment blocks while clad only in hooded leather ponchos, with thick rawhide gloves and aprons, stout boots, and a damp cloth secured over the mouth to fend of the choking heat and toxic fumes.

Just as today though, these imperial firefighters probably suffered frequent slips, trips, and falls. And no doubt many died from asphyxiation, crush injuries, bone fractures, and burns — complicated, of course, in an era without antibiotics, by the deadly infections that subsequently attend these types of insults. But what about job-related cancers?

Large, real-time, statistically significant epidemiological studies linking cancer to fires would have to wait for another two thousand years. Or, until 1775, when British surgeon Percival Pott (1714 – 1788), published a startling description of the agonizing and fatal cancers associated with prolonged exposure to smoke and soot — cancers that routinely consumed young chimney sweeps during the industrial revolution in England. We will return to Pott and his findings in due course.

■ Did Ancient Firefighters Live Long Enough to Develop Cancer?

Cancer often, but not always, takes decades to develop, even when people are exposed to carcinogens on a daily basis. In my practice as an oncologist, I recall seeing many patients present with lung, or the myriad other smoking-related cancers, in their early seventies, after fifty years or more of concerted tobacco consumption. Cancer, in the public at least, is usually a disease of advancing maturity. In Canada and the U.S., about 90 per cent of cancer diagnoses occur among individuals who are at least 50-years of age or older.

Therefore, did Roman firefighters, with a lifespan that was probably quite short, even live long enough to develop line-of-duty cancers? We have no direct information, even though tens of thousands of professional firefighters lived and died in a multitude of Roman cities over the five centuries that the imperial fire service flourished. No data was captured — no medical or epidemiological observations were ever chronicled, for the sake of posterity, to enlighten future generations as to the various ways in which these firefighters were injured or died.

Some indirect information, however, comes to us from construction of the 300 km/h Rome to Naples high-speed railway, completed in 2009. These excavations would allow a multidisciplinary team of Italian researchers, including medical historian Valentina Gazzaniga, at the Sapienza University of Rome, to finally make some informed observations about the harsh, even brutal realities of life as it concerned the Roman proletariat. A suburban, working-class graveyard from the first and second centuries was uncovered that contained the skeletal remains of about 1,800 Roman blue-collar workers — their bones were systematically examined by visual inspection, CT scanning, and plain radiographs. The grim news was that the average workers — and this would surely include the firefighters of Rome — were dead by the median age of 30. The skeletons harboured conditions and diseases that physicians of today still commonly see: arthritis, bone infections, nutritional deficiencies, metabolic bone diseases, severe fractures of the nose, hands, limbs, and clavicles, and “a really high incidence of bone cancer.” Cancer of the soft tissues or internal organs will dissolve away with time as the body decomposes, but cancer that starts in or spreads to the bones, well, that can be preserved in the forensic anthropology records forever.

These striking observations regarding injuries, chronic illnesses, and cancer in the Roman working class may explain why imperial Roman firefighters were celebrated and rewarded if they withstood a daunting six-year stint in the fire service. Six years, that is, if they were fortunate enough to last that long. Recognizing this, the barrier was subsequently lowered by the imperial Roman government to a presumably more survivable three-year span of service, after which the firefighters were entitled to a lifetime supply of free grain as supplied by the emperor.

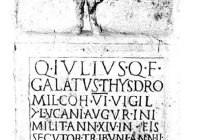

A shortened life expectancy in the professional Roman fire service may have been inadvertently captured by the assistant fire chief Quintius Julius Galatus, who probably had his gravestone and most of his epitaph carved before he died (see photo): Quintius Julius Galatus, from Thysdrus in Africa, served in the 6th fire brigade of the City of Rome under the authority of fire chief Lucanius Augurinus. He served a total of 14 years, and during that time he was an attendant of the fire chief for 2 years, then one of his special agents for 2 years, and then rose to the important rank of fire attack director for 3 years. He lived only 37 years.

As an experienced, 14-year veteran firefighter, Galatus was painfully aware that death could come unexpectedly and at any time.

■ How Long Does It Take to Develop an Occupational Cancer?

Returning to the British surgeon Pott, it may have been fortunate for science that he was thrown from his horse in 1756 and suffered a severe fracture of his ankle. Pott was thereby confined to a significant period of bedrest, during which, to while away the hours, he began to write medical publications regarding the various clinical conditions he had encountered during his surgical practice. Were it not for that broken ankle, and the satisfaction he subsequently derived from medical writing, the recognition of an occupational link between environmental carcinogens and cancer — “I mean the chimney-sweepers’ cancer” — he emphasized, may have had to wait for some future generation to document. Percival Pott’s 1775 medical publication, “Chirurgical Observations relative to…cancer of the scrotum”, marked the beginnings of an epidemiological link between environmental carcinogens and job-related cancers. His account describing the plight of these young chimney sweeps was heart-wrenching and compelling.

“The fate of these people seems singularly hard; in their early infancy, they are most frequently treated with great brutality, and almost starved with cold and hunger; they are thrust up narrow, and sometimes hot chimnies, where they are bruised, burned, and almost suffocated; and when they get to puberty, become peculiarly liable to a most [unpleasant], painful, and fatal disease… cancer of the scrotum and testicles.”

Pott describes in fascinating detail how cancer is caused by soot that accumulates in the skin folds and begins somewhat after puberty as a raw and ragged ulcer involving the scrotum. This lesion then spreads quickly over the surrounding skin, penetrating deep into the muscles and membranes of the scrotum. Next, the cancer infiltrates, enlarges, and hardens the adjacent testicle, thereafter ascending up the spermatic cord to involve the lymph nodes of the groin, and from there disseminating into the viscera of the abdominal cavity. Even with early, aggressive surgical removal of all visible disease, followed by excellent healing of the incision and subsequent discharge from the hospital in good health, Pott relates that the disease returns with an inevitable fatality:

“In the space of a few months, it has generally happened, that they have returned [to hospital] either with the same disease in the other testicle, or in the glands of the groin, or with such wan complexions, such pale, leaden countenances, such total loss of strength, and such frequent and acute internal pains, as have sufficiently proved a disease state of some of the viscera, and which have soon been followed by a painful death.”

Although the youngest patient documented by Pott and his colleagues was an apprentice chimney sweep of only eight, most of these young men developed job-related cancers after the age of 20, and usually before the age of 40. As a medical oncologist, I have observed that many occupational cancers, such as those involving firefighters, can sometimes present earlier in life and are often more aggressive and more treatment resistant than the ‘sporadic variety’ of cancers that arise in the general public.

The importance of Pott having established such a relationship was that it eventually led to public acknowledgement of the problem, followed by changes to, and improvements in working conditions. In fact, a concerned British Parliament, motivated to the point of uproar, passed The Chimney Sweepers Act of 1788. This was a new labour law that prohibited the exploitation of orphaned or impoverished children, some as young as four years old, who, without proper food, clothing, or personal protective equipment, were forced to work long and dangerous hours cleaning hot, toxic, soot-encrusted chimneys.

Fortunately, “the chimney-sweepers’ cancer” died out as a frequently encountered clinical entity in the early twentieth century, probably because of alternative methods of heating, improved hygiene and working conditions in the chimney sweep trade, and better methods of cleaning chimneys. However, the scourging legacy of “the chimney sweepers’ cancer” lives on today in spirit, as reflected in the higher incidence of cancer in modern firefighters — and the startling mortality rates that are so often solemnized in bell ringing ceremonies all over Canada and the U.S.

■ Today’s Carcinogens are More Toxic, and the Fires are Raging Hotter

In terms of professions, 1st century Roman firefighters are not eighteenth-century chimney sweeps, and young chimney sweeps of the 18th century are not our modern 21st century firefighters, but one heartbreaking fact units them all. Each of these groups of hardworking and earnest individuals share something common in the dimensionless bonds of eternity — they have all had to withstand unavoidable work-related risks and hazards that render them dramatically more vulnerable to certain illness and injuries, including job-related cancers. And although the professional firefighters of today are probably better trained, more highly educated, outfitted with state-of-the art equipment and bunker gear, and schooled in the lore of situational awareness, the fires of today are burning hotter, higher, more dangerously, and superbly more toxic than ever before in history.

Print this page