Features

Understanding Stoicism

The philosophy behind developing a positive cognitive lifestyle

July 2, 2021

By Nick Halmasy

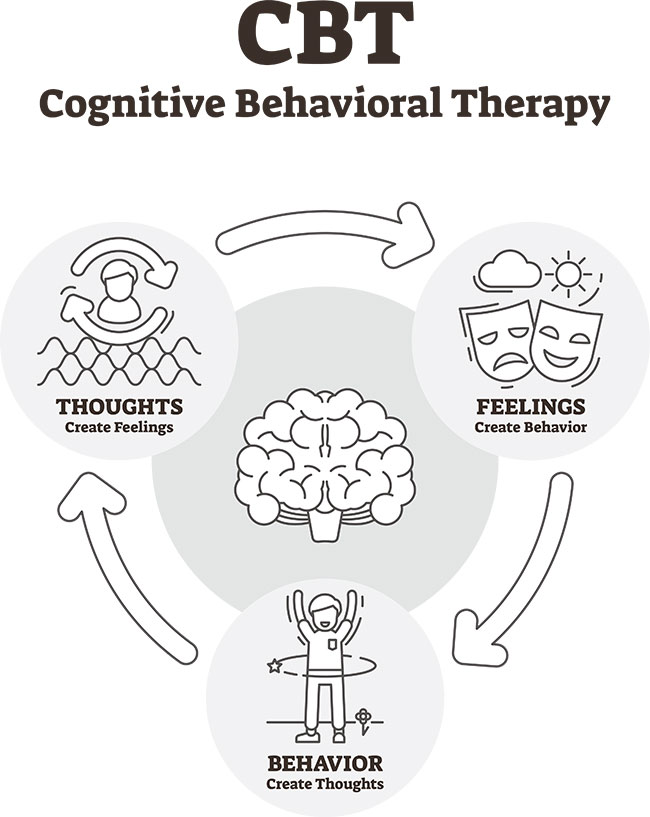

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, or CBT, is the most valid, well-research approach we have. Photo credit: hafakot/Adobe Stock

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, or CBT, is the most valid, well-research approach we have. Photo credit: hafakot/Adobe Stock I’ve played guitar, rather spuriously, for the better part of my adult life. Introduced to music at a young age, I still own, and sometimes play, the few guitars that I have. There is a marked decrease, however, in the skills and songs that I used to know. I guess, in some instances, if you don’t use it, you do lose it.

Why, we may wonder, do we continuously practice our first aid and defib? Or, even though it’s superiorly boring in relation to, say, forcible entry, do we continue to practice pump operations? You got it, after all, right? What more can we learn?

In clinical practice, we are teaching “skills and tools” for individuals struggling with mental health. This, in fact, is often the preamble to selling someone on entering into therapy, isn’t it? “This is hard, and will be hard, but at the end we hope you have the skills and tools…” is the script for any structured therapy process.

I say it and my colleagues say it. I’ve come to understand that we are underselling the resources that we have at hand. In fact, it’s also the way you have been introduced to mental health, mental wellness, and mental health programs and trainings. Skills and mental tools is accurate but what about practice makes perfect?

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the largest, most well-researched, reliable and valid approach to mental health that we have. Almost any “new” approach comes reliably from the philosophy of CBT and its approach to treating mental health. And, there is a reason for that. It was one of the first psychotherapies that treated the holistic individual, in understanding that there are three components to mental wellness to be addressed: emotional, cognitive and behavioural. These interplay with each other. None is a standalone, and there is no linear process. Just like basic fire chemistry, you need a few components to start a fire, but to keep it going, or to grow it, we need a continuous interplay of the components.

But, like playing guitar, defib, or pump ops, skills and tools are susceptible to metaphoric rusting. Imagine, for instance, if all we needed was a single CPR course and and we never looked at those processes again. We roll up on a VSA. Can you imagine you would be adept? No, which is why we’re put through the ringer a couple times a year.

What does this have to do with anything? Well, I’m attempting to change the conversation of mental wellness to capture this deeper understanding. This will be a three-part series on developing a “cognitive lifestyle” that works to prevent the rusting of those skills and tools you develop. We’ll have a mixture of areas that inform this process, including research, clinical skills and philosophy. This article will explore the behavioural side, the next will look at the emotional realm and lastly, we’ll venture into the cognitive.

Firstly, we should ask ourselves whether the concept of cognitive lifestyle is a “new” idea or not. I certainly haven’t heard it spoken about in this way before on any recent medium, be it news or otherwise. It isn’t new, though. In fact, it’s pretty darn old. Thousands of years old.

In the days of the toga being a pretty stellar wardrobe option, philosophy was at its pinnacle. And, back then anyways, philosophy was more than bearded men smoking pipes and pondering the universe — it was a way of life and being. Philosophy was often conducted in the gymnasium, where sedentary life was unvirtuous and its interests were vast. There are plenty of different, interesting philosophies to look at, but only one concerns our present day problem.

Stoicism.

Now, before we dive too deep, let’s face the biggest misconception to this word. You likely understand, as I did, Stoicism to be the emotionless approach to things. To be stoic is to wear problems and issues free from any emotion at all (I argue this is impossible, but regardless, this is what we see this as). In fact, our beloved ideal of the salty firefighter presents us with just that frame. The problem is that this has been a major misconception of the Stoic philosophy.

“Their goal wasn’t to banish emotion but to minimize the number of negative emotions,” writes William B. Irvine in his book The Stoic Challenge. Compare that with a modern-day CBT slogan: “CBT is based on the concept that your thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and actions are interconnected, and that negative thoughts and feelings can trap you in a vicious cycle.” (This was taken from the National Health Service in the UK, where they have had a long publicly funded CBT program with huge success.) Oh, and we now have such a program too, at least in Ontario. If you are interested, look up Ontario’s Structured Psychotherapy Program. It’s free.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s get down to why the marriage of a lifestyle-like approach like Stoicism combined with a tried and true therapeutic approach is highly likely to provide you with the lasting and necessary cognitive muscle memory to continue to thrive and grow in your career. What might our first step be?

The behavioural

The emotional and cognitive facets will need their own space, so we’ll start with the least intensive, though still important component. We don’t often think of our behaviour as being an important component to our mental health, but we should (go back to see what I wrote on exercise and the prevention of PTSD in the March 2018 edition of Fire Fighting in Canada). It is, however, integral to our mental health for various reasons, the largest being that our behaviour may actually make us sicker.

In treatment for almost all kinds of mental health, we help people to identify what they are avoiding. Now, this may seem obvious, but it isn’t always. Avoidance takes on many different forms. For instance, seeking reassurance about something is a form of avoidance, especially when you know know you are doing something correctly, but feel compelled to “double check”. Over time, this can sensitize us to the uncomfortable feeling of doubt, lower our threshold for tolerance, and produce reassurance seeking more often and more quicker. Accumulating over time, this develops into a difficult-to-overcome habit of avoiding uncomfortable situations, and this then starts to generalize.

Avoidance of triggers to a traumatic event is a component of the diagnosis of PTSD, but is also a common trait in anxiety, generally. Looking at this from a strictly CBT lens, we would address the underlying avoidance (i.e. asking you to confront otherwise objectively safe situations). This is known clinically as exposure, which is a skill you would practice until your distress came down and the new learning about that situation was ingrained. The downside is that after treatment is done, we can quickly become complacent and begin to fall back into these old behavioural habits. I call this the antibiotic effect. The Stoic requests that we consistently engage in these things, as a matter of daily habit.

You see, the thing that you may avoid isn’t actually the source of your suffering, it is the emotional experience that we have attached to that thing. We call these emotionally driven behaviours. They are important in understanding and overcoming the fears that we experience, be it from trauma or anxiety, or on the other end, where we may find that we are just beginning to develop these unhelpful habits. Recognize that the emotions you are experiencing may not be telling you the truth about the reality (dangerous situation versus objectively safe situations). The Stoic understands that “we don’t react to events; we react to our judgments about them, and the judgments are up to us,” as eloquently stated by the philosopher Ward Farnsworth.

We don’t need to pray for constant tragedy to befall us regularly in order to practice either. Practice requires us to focus on the small events, building confidence and trust in our abilities in an effort to be able to use them on the big events. One interesting behavioural solution was proposed by Donald Roberston, author of How to Think like a Roman Emperor, in an interview on UpTalk podcast. Robertson suggested that we act as if the troubling event occurred a year ago. We are providing a distance that time provides, but using our agency to expedite the process. Behaviourally, we are challenging ourselves to act (and think, because we can’t be without it) as if you are not tackling the hard thing for the first time, but instead tackling it for the hundredth time, and how you may act and approach those situations. Experience, especially when performed from a positive, adaptive angle, is a great teacher.

We’ve broken down the misconceptions that may lay between an understanding and open mind with regards to an ancient way of living, combined it with its modern analogue, and examined why it makes more sense in the long run to view any mental wellness approach to be one of a cognitive lifestyle change, versus the collection of tools to be employed at sporadic and periodic points of time.

Here’s your homework:

- Pay attention to your behaviour. Do you avoid unknown callers, certain work-related tasks, certain conversations, different issues, old locations of calls, etc.?

- If you are struggling with motivation, plan out specific behaviours on a weekly schedule and follow that plan, not your mood. Pay attention to your motivation changes.

- Do something uncomfortable. Put yourself in that situation. Pay attention to what you learn about it.

- Track all of this for reflection.

Nick Halmasy is a registered psychotherapist who spent a decade in the fire service. He is the founder of After the Call, an organization that provides first responders with mental health information. Contact him at nhalmasy@afterthecall.org.

Print this page

Advertisement

- Majority of Lytton, B.C., destroyed in fire

- Federal government providing assistance to British Columbia for wildfires